|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

|

LISTEN TO AUDIO VERSION:

|

Background to the AI Liability Directive

In Finland in 2018, a customer sued his bank for discrimination before the Non-Discrimination and Equality Tribunal of Finland because it had refused to grant him a loan. The tribunal ruled in favor of the plaintiff, in part because protected characteristics such as gender, native language, age, and place of residence had been used and had led to the credit denial[1].

In future, situations like this may well end up in court more often: In cases where the results generated by AI systems[2] are suspected to cause damage, the European Commission wants new liability rules to apply, under which the burden of proof could lie with the financial institution. To what extent will the new AI Liability Directive affect the already highly regulated financial industry – also in Germany?

Presumption of causality and right of access to evidence are meant to increase the level of protection

In the case of claims for damages, generally the cause of the damage must be explained, but this is very difficult due to the “black box” effect of AI applications. In the explanatory memorandum to the Directive, the European Commission states that unclear AI liability rules are a major barrier to the use of AI in financial institutions. To ensure an equivalent level of protection for damage involving AI and not involving AI, as well as to promote innovation, the AI Liability Directive is to be adopted.

It consists of two main components:

- One is the presumption of causality, which establishes a direct connection between non-compliance with a duty of care and the damage incurred. For this purpose, the claimant must prove that several requirements are fulfilled: First, non-compliance with a relevant duty of care must be shown. Then, it must be “reasonably likely”[3] that the erroneous behavior of the AI has influenced the result and finally led to the damage. If the presumption of causality is established based on this evidence, the defendant may prove their innocence by rebutting this presumption.

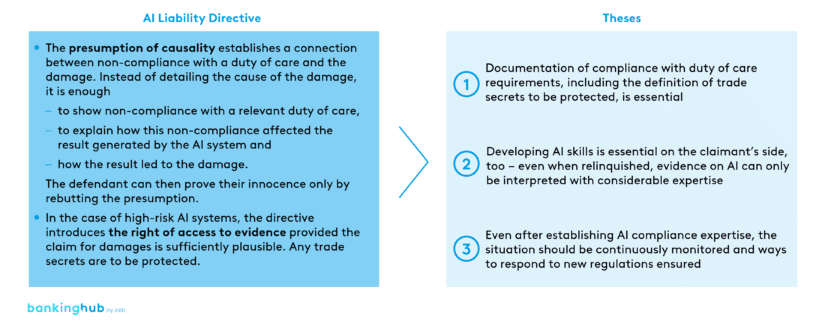

- In the case of high-risk AI systems[4], the right of access to evidence – the second component – provides the claimant with another means to make their case. Claimants are allowed to request disclosure of evidence on AI systems, provided that there is “evidence sufficient”[5] to support the plausibility of a claim for damages. The rights of the defendant regarding the protection of trade secrets and confidential information are to be explicitly taken into account – the disclosure of evidence is to be “necessary and proportionate”[6]. If a defendant does not comply with this obligation to disclose, it is presumed that the defendant is in non-compliance with a relevant duty of care, which would already fulfill the first requirement for the presumption of causality to apply. Again, the defendant has the right to rebut the presumption. As a result of these legal rules, three key theses can be derived that are gaining importance for financial institutions (see Fig. 1):

Thesis 1: Documentation of compliance with duty of care requirements, including the definition of trade secrets to be protected, is essential

The key prerequisite for rebutting the presumption of causality is compliance with the duty of care relevant in the context of the damage. To prove compliance, the defendant must have documentation that demonstrates compliance with their duty of care.

However, the current liability directive largely leaves open what the specific duties of care and related documents are. Only for high-risk AI systems are the duty of care requirements specifically defined by making reference to the Artificial Intelligence Act (e.g. quality criteria for the use of AI training datasets). For other AI systems, however, reference is made only to national and EU law. However, in this case too, it is advisable to use the Artificial Intelligence Act as a guideline, as it is closely linked to the liability directive.

In the case of high-risk AI systems, it should additionally be noted that all relevant evidence must be disclosed upon the claimant’s request – limiting the scope of this disclosure to a “necessary and proportionate”[7] extent can likely be facilitated by consistent and precise documentation of the way the AI system and its components work. This applies in particular if the potential evidence includes confidential information or trade secrets. Trade secrets should therefore be clearly identified as such so that, even years after preparing the documentation, no institutional interests are violated in the event of disclosure.

Thesis 2: Developing AI skills is essential on the claimant’s side, too – even when relinquished, evidence on AI can only be interpreted with considerable expertise

Financial institutions are, of course, not only potential providers of AI systems, but also users. And while the directive is intended to make it easier to bring a liability claim in an AI-induced case of damage, extensive knowledge on the part of the claimant remains essential. After all, it is still up to the latter to prove non-compliance with relevant duties of care and to assess whether the overall circumstances of the damage allow the presumption of causality to be applied.

Furthermore, in the specific case of high-risk AI systems, the presumption of causality may be suspended, if “sufficient evidence and expertise is reasonably accessible”[8] for the claimant – in which case it is up to the claimant to prove the causal link themselves.

Thesis 3: Even after establishing AI compliance expertise, the situation should be continuously monitored and ways to respond to new regulations ensured

The current draft directive sets out a clear direction, but changes may nevertheless be made before it is adopted by the European Parliament and the Council of the European Union. Furthermore, the interpretation of some of the wording is currently not yet clear: When is the “evidence sufficient”[9] for a claim for damages to be regarded as plausible? What types of evidence or trade secrets are “proportionate”[10]? How is “considered reasonably likely”[11] to be interpreted? Close monitoring of relevant case law and new regulations or amendments is therefore necessary.

BankingHub-Newsletter

Analyses, articles and interviews about trends & innovation in banking delivered right to your inbox every 2-3 weeks

"(Required)" indicates required fields

Creation of legal certainty through AI Liability Directive is to be welcomed

As explained in the directive, the unclear legal situation regarding liability issues is currently a major obstacle for using AI in financial institutions. According to zeb opinion, the draft directive offers an approach that creates more legal certainty, but at the same time increases the liability of financial institutions – in particular, the presumption of causality may in real life correspond to a mitigated reversal of the burden of proof.

Nonetheless, there are currently few use cases among financial services providers where the AI Liability Directive in its current form would have a material impact – primarily because of the considerable regulation already in place. For example, there are already extensive mechanisms for creditworthiness checks, which include comparable protective functions for applicants. What is important, therefore, is to consider the requirements of the AI Liability Directive at the very beginning of developing new AI solutions.