Bond issuance as a strategic decision

The issuance of a green bond affects a bank’s entire value chain. As a first step, we recommend conducting a preliminary study that consists of a market, sales and profitability analysis. Not least, the goal of this study should be to determine whether there are any capital market instruments that meet the objectives associated with the planned issuance, and if so, which one is best suited in that regard.

When it comes to green bond issuance capability, each institution has its own goals and expectations. These should be assessed in a structured manner. For the assessment, various aspects should be taken into account, such as:

- Profitability (e.g. initial and ongoing costs, expected issuance volume, revenue model)

- The bank’s sustainability goals – and the extent to which the program contributes to achieving those

- Diversification of funding sources (acquisition of new customers / sales markets)

- Reputational/Marketing benefits (incl. consideration of possible greenwashing effects/accusations)

- Potential/Availability of green bond-eligible collateral

- Strategic options (e.g. alternatives to or medium-term consequences of green bond issuance capability)

It might turn out that a traditional use-of-proceeds instrument[1] (i.e. an actual green bond) is less well suited to the needs of the bank or the nature of the collateral than, for example, a sustainability-linked bond (SLB)[2]. If a bank wants to address rather concrete sustainability objectives in its operations and measure them accordingly, an SLB might be a useful and much simpler alternative to traditional use-of-proceeds instruments, because SLBs do not require any concrete restrictions on the use of funds nor a pool of eligible collateral.

In light of the regulatory developments of recent years, banks should keep in mind that in the long run, green bonds might become the standard way of raising funds rather than the exception. Therefore, it can be assumed that the demand for conventional bonds without sustainability requirements will decline.

BankingHub-Newsletter

Analyses, articles and interviews about trends & innovation in banking delivered right to your inbox every 2-3 weeks

"(Required)" indicates required fields

Green financing: achieving green bond issuance capability

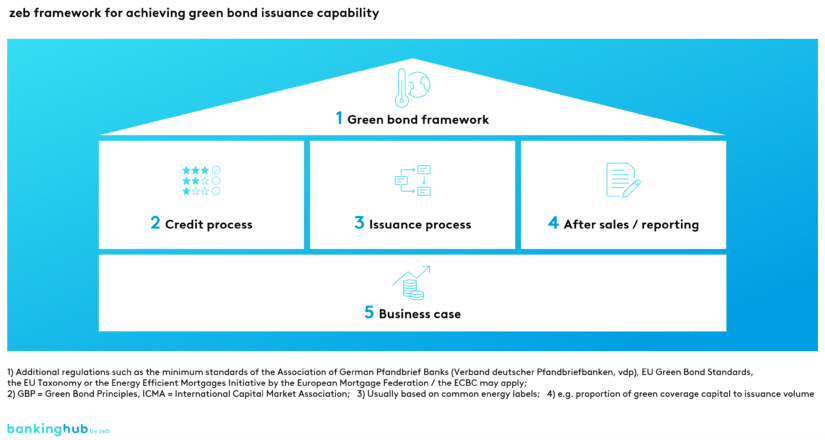

Based on previous experience, zeb has developed a best practice model for achieving green bond issuance capability. At its core, this model consists of five modules (see figure 1).

Module 1 – the business case

Based on the results of the preliminary study, the bank should develop a detailed business case from which a clear go/no-go decision can be derived. When preparing the case, different scenarios and options (e.g. products, markets, current/target portfolio) should also be considered in order to obtain a realistic picture of the potential issuance volume and spread advantage. If the bank does not primarily pursue economic goals, the costs of its non-economic goals can be calculated instead.

A significant earnings potential lies, for example, in the funding cost advantage resulting from the spread (the so-called “greenium”), whose magnitude depends on the respective asset class. According to current external studies, the greenium is between 1 and 10 bps (see excursus). If the demand for green bond investments grows faster than the supply, the greenium might even increase beyond that. The additional costs compared to a standard bond are primarily due to internal process and system adjustments, second party opinion (SPO) costs and internal or external impact reporting. After all, it is crucial to provide a realistic range for the key assumptions that are subject to the greatest uncertainties and to calculate different scenarios in the business case.

Excursus on the spread advantage

A study by Dorfleitner et al. (2021)[3] suggests a spread advantage for green bonds in the range of 1 to 5 bps, which varies, in particular, with the transaction’s SPO rating (e.g. “dark/medium green” categorization). Another study by Huynh et al. (2022)[4] calculated a greenium of 3 bps based on a matching procedure with 161 green bonds between January 2016 and March 2021.

Moreover, the Federal Republic of Germany issues twin bonds, i.e. a green security and a conventional one with otherwise identical characteristics, e.g. in terms of their maturity.[5] For those, a greenium of 2 to 10 bps could be observed in the period from August 2022 to July 2023.

However, there are also studies such as Zimmermann/Rohner (2021)[6] that have determined a much higher greenium of 30 bps based on a matching procedure for 57 bonds.

Module 2 – definition of the green bond framework

When selecting eligible green collateral, banks must decide on a regulatory framework under which to issue the respective green bond. In this context, the Green Bond Principles (GBP)[7] established by the ICMA[8] are regarded as minimum standards. Institutions that are defining their own green bond framework must adhere to these Principles. In addition, banks are well-advised to consider whether the bond to be issued should, for example, also comply with the (future) EU green bond standard (EUGBS)[9]. In addition, if the bond is to be issued as a Pfandbrief, it might also make sense to meet the minimum standards of the Association of German Pfandbrief Banks (Verband deutscher Pfandbriefbanken, vdp).

Excursus on the ICMA’s Green Bond Principles (GBP)[10]:

- Principle 1: The issue proceeds are earmarked for purposes that fall within one or more of the nine predefined green asset categories.

- Principle 2: The project selection and ESG assessment processes must be fully disclosed.

- Principle 3: The separate management of revenues and the internal processes for adherence with Principle 1 must be ensured.

- Principle 4: The issuer is obliged to report on the bond at least annually until the funds are fully expended.

Module 3 – adaptation of the credit process

Usually, the credit process needs to be adapted to the defined framework and the selected products/markets. This includes, for example, changes to the documents to be obtained to account for organizational changes as well as the training of sales staff.

Many banks are paying particular attention to credible certification of the sustainability requirements for new loans, as this business offers the greatest potential for financing green collateral. To this end, banks can, for example, rely on external classifications. When it comes to mortgage financing, the energy performance certificate required by the German Buildings Energy Act (Gebäudeenergiegesetz, GEG) is a suitable classification instrument, while in cases of high complexity, even sophisticated ESG scoring approaches might be a viable alternative.

Module 4 – setting up the issuance process

Before banks can implement the issuance process itself, operational questions need to be answered including how to ensure traceability and the appropriate use of funds as well as which SPO or, if necessary, which additional green bond issuance rating to go for.

Module 5 – reporting

In order to comply with the reporting and monitoring requirements, the necessary content must be collected and prepared. In this context, zeb recommends fleshing out the impact reporting concept early on in the project to identify the resulting data requirements and ensure their fulfillment within the credit process so that the impact to be assessed can actually be traced. In addition, the question of whether to “make or buy” the reporting process – especially when it comes to impact reporting – arises, as there are various providers on the market to which it can be outsourced. This decision heavily depends on the internally available expertise in handling ESG data.

Processes for the issuance of other use-of-proceeds bonds such as social or sustainable bonds can be set up in a similar way. Despite various overlaps, there are inherent differences between use-of-proceeds and performance-linked bonds. Banks that issue the latter can thus forgo several checkpoints such as the traceability of cash flows.

Summary

- Green bond issuances affect the entire value chain due to the associated assets and agreements. Therefore, banks need to make a fundamental strategic decision.

- The earnings and cost dimensions of a green bond issuance must be carefully weighed up, as, for example, the magnitude of a potential greenium, which constitutes the basis for the associated profitability calculation, depends heavily on the market situation.

- While the ICMA’s Green Bond Principles are de facto binding, banks must decide whether there are additional benefits to complying with further and stricter standards.

- Issuing green bonds requires various adjustments to existing processes, which is why outsourcing specific process steps to third parties could be advantageous for some issuers.

- Due to the current market developments, we consider it inevitable to at least look into the possibility of achieving green bond issuance capability.