|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

Operational costs of regulation overwhelm medium-sized institutions

Since the beginning of the financial market crisis, institutions have had to deal with very extensive and dynamic regulation. International bodies develop new regulatory initiatives for the regulation of large international banks (the “cause of the financial market crisis”). These regulations are mandatory for all institutions via the European supervisory system (“one size fits all”) and therefore also apply to medium-sized institutions. The operating expenses associated with new regulations are disproportionately high for medium-sized institutions that operate under simple and low-risk business models aimed at medium-sized enterprises (SME) and real estate financing. Regulators and politicians have recognized the need to strengthen the proportionality principle in the regulation of medium-sized institutions.

Already in the spring of 2016[1] the German Minister of Finance publicly proposed regulatory simplifications for medium-sized, less complex institutions. Since then, politics, supervision and industry have discussed alternatives in order to design a regulatory area with simplified and basic requirements, specifically geared to the regulation of medium-sized institutions (commonly referred to as small banking box).

The simplifications for medium-sized institutions that are currently being discussed aim at the actual problem, namely at the mitigation of operational encumbrances and not at a reduction of capital and liquidity requirements.

In the following, two possible regulatory approaches of a small banking box design are presented. Finally, important issues are addressed that need to be answered for the specific design of the small banking box.

Approaches to proportional regulation of institutions

Proportional regulation means that regulatory requirements are based on the size and complexity of an institution. It refers in particular to procedural requirements (such as reporting requirements), the fulfillment of which is comparatively expensive for smaller institutions.

In general, when proportional regulation is applied, the same rules should apply to the same risks, irrespective of the size and type of business activities of an institution. Since smaller institutions with comparatively simple business models pose lower risks to financial stability, lower requirements can be placed on this group without endangering the objectives of regulation.

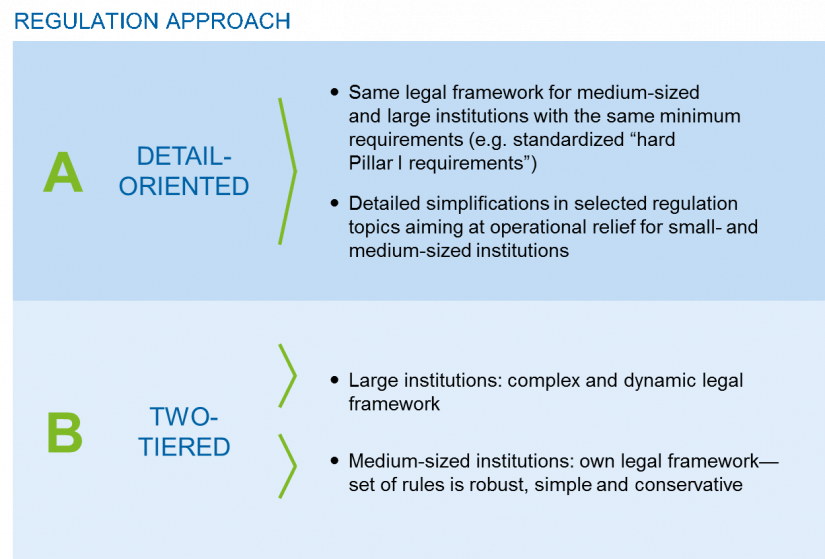

Currently, two approaches to proportional regulation are being discussed. The first proposal—the detail-oriented regulation approach—takes as its basis the existing regulatory framework and extends it to topic-based simplifications / exemptions for medium-sized institutions (see figure 1). The second proposal—the two-tiered regulation approach—aims at a distinction of the regulatory framework, each with its own rules, for medium-sized and large international institutions.

Detailed-oriented regulation approach

The detail-oriented regulation approach states that medium-sized and large institutions are subject to the same regulatory legal framework and therefore to uniform minimum requirements (same “hard” pillar I requirements). In selected regulatory issues, however, the detail-oriented regulation approach contains simplifications with the aim of providing operational relief to medium-sized institutions. Special exceptions or adjustments for selected requirements should reduce procedural burdens in medium-sized institutions. In the following, essential topics for the design of more proportionality are presented and their significance for the institutions is explained.

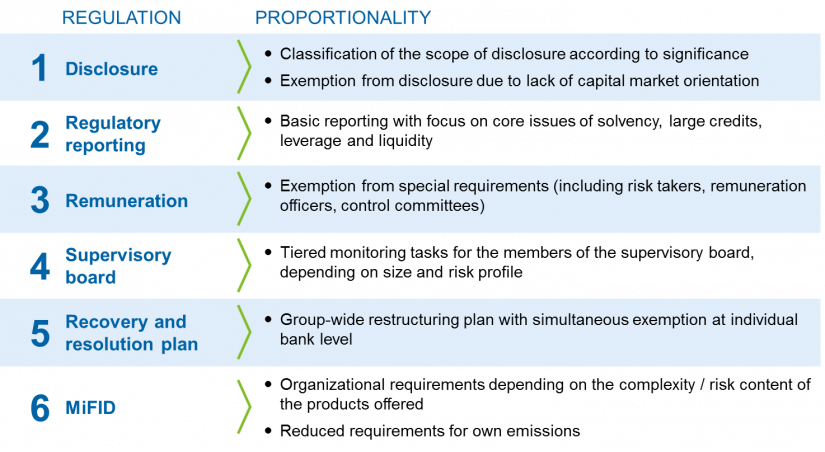

In the case of (1) disclosure, proportionality is justified with the ownership structure of medium-sized institutions and their lack of capital market orientation. In general, institutional investors, as typical recipients of a disclosure report, play no or only a minor role. Moreover, the general public shows only little interest in disclosure reports—a disciplining function directly from the market, therefore, cannot be expected.

In (2) regulatory reporting, the high complexity, the lack of consistency between the CoRep reports and the high volume of individual reports pose a constant challenge to medium-sized institutions. Precisely because the objectives of supervision can be achieved for smaller institutions with a significantly reduced reporting scope, the creation of a basic reporting system for medium-sized institutions (focusing on core figures of solvency, large credits, leverage and liquidity) offers a practical approach to operational relief.

In parts, the current draft of the new CRR and CRD have already taken proportionality in disclosure and regulatory reporting into account. The included simplifications and thresholds for disclosure and regulatory reporting requirements for institutions with less than €1.5 billion of total assets (average over the past four years) are a prominent example of simplified requirements.

Regardless of the proportionality aspect, a systematic revision of reporting requirements with the focus on eliminating overlaps would be advantageous in this context, not least because they also benefit large institutions. So far, new reporting requirements have been designed largely per topic and less with regard to increasing regulatory efficiency. Synergies between single reports could be leveraged by consolidating comparable data requirements. In this way, operational “duplication” would be avoided.

Another topic currently being discussed is proportionate (3) remuneration regulation[2]. The basic tenor is that medium-sized institutions offer only limited incentives for risk takers[3] to take disproportionately high risks (moral hazard), since variable remuneration plays only a subordinate role. In these institutions, the gap between the salaries of executives and employees is lower. Moreover, the required disclosures on the salary structure at small institutions would allow inferences about the remuneration of individual employees at operational level, which seems disproportionate[4].

With regard to the requirements of the (4) supervisory board, it can be argued that the prerequisites for the supervisory board members for an informed perception of the control function at medium-sized institutions are not comparable with large banks and their complex business models. Tiered supervision obligations are therefore proposed for members of the supervisory board depending on the size of the institution and its risk profile. Appropriate, individual requirements would have the effect of easing and would also allow the actual regulatory objective to be achieved. For the sake of simplification, the different prudential requirements for the structure of remuneration systems and the suitability of members of the management body and the holders of key functions / risk takers could also be consolidated.

On the subject of (5) recovery and resolution plans, the current proposals are aimed at providing extensive relief for smaller institutions. Historically, the group-wide deposit guarantee schemes of medium-sized institutions have made their intended impact. The financial distresses of individual medium-sized institutions have been absorbed by intra-group deposit guarantee schemes and have barely led to taxpayer burdens in Germany. For this reason, there is currently a call for a group-wide reorganization plan with simultaneous exemption at individual bank level.

The requirements for investor protection, competition and the harmonization of the financial market also offer room for more proportionality: (6) MiFID II/MiFIR cause particularly high procedural costs in medium-sized institutions. Main drivers include extensive documentation and information requirements for selling financial products in connection with the German Fees for Investment Advice Act, which goes beyond EU regulations. For this reason, there is currently a plea to adapt the requirements for smaller institutions to EU level.[5]

As can be seen from the selected topics, some measures have already been taken on the way to a more detail-oriented approach. In this context, provided the actors involved could reach agreement on the content, it would thus be possible to quickly implement the proposals. However, this should not distract from the consideration of an alternative approach, which basically provides its own rules for medium-sized institutions.

Two-tiered regulation approach

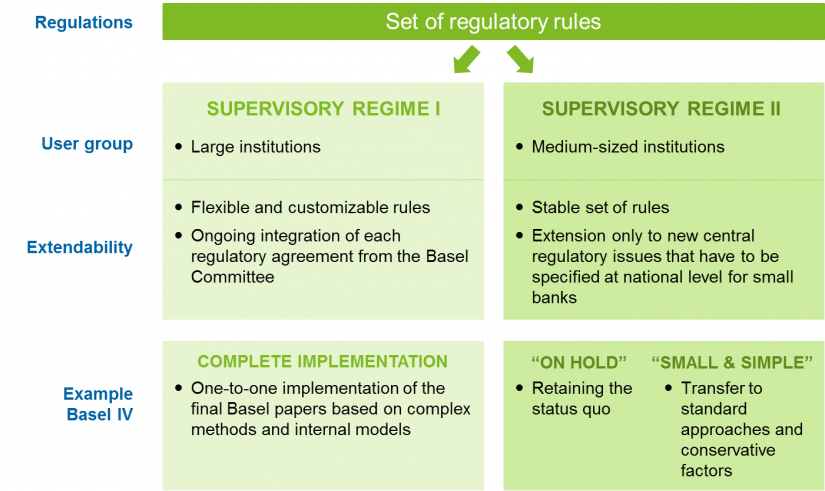

The two-tiered regulation approach is characterized by independent supervisory regimes for large and medium-sized institutions. Large institutions are subject to a complex and dynamic supervisory regime. Medium-sized institutions are, in turn, supervised by an independent set of rules that is robust, simple and conservative.

Large institutions are regulated by a flexible and adaptable set of rules (supervisory regime I, see figure 3). Due to the fact that the regulations developed by the Basel Committee are specifically designed and geared towards large international banks, all new initiatives from the Basel Committee are incorporated into the supervisory regime I for large institutions.

The supervisory regime II for medium-sized institutions is stable and robust and is based on standard approaches with conservative calibration. Another important feature of the set of rules for medium-sized institutions is the simple comprehensibility of the regulatory requirements (laws, guidelines, circulars, consultations) in the official language(s) of each country.[6]

A further development of the rules and regulations for medium-sized institutions is only carried out for new central aspects of regulation whose targets had not been covered by the existing regulations or not sufficiently. Every new Basel initiative will be reviewed to gauge whether the set of rules can be extended to medium-sized institutions. The review may show that the existing set of rules is sufficiently robust and therefore does not require any enhancement (“on hold”). However, if an extension is required, a Basel proposal will be included on simple standard approaches with conservative factors and robust calibration (“small and simple”).

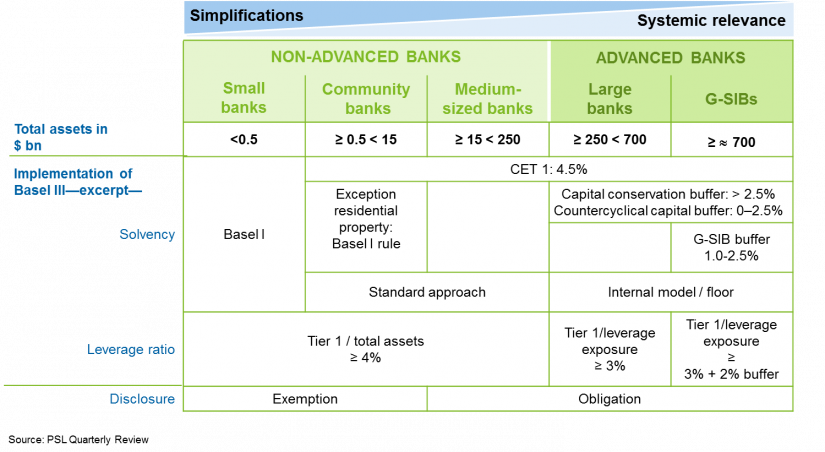

The two-tiered regulation approach is already established in other countries, as illustrated in the practical example of implementing the minimum requirements under Basel III (solvency, leverage ratio and disclosure obligation) in the US banking supervisory system. This two-tiered regulation approach differentiates between

- “non-advanced banks”—small and medium-sized institutions with up to $250 billion of total assets and

- “advanced banks”—large and international institutions with total assets above $250 billion.

The figure below illustrates how institutions, following the principle of proportionality, must increasingly comply with Basel III requirements in proportion to an increase in their total assets and systemic importance:

The smallest group of non-advanced banks includes institutions with assets below $0.5 billion, known as small banks. Small banks calculate solvency according to the rules of Basel I, i.e. also the standard approaches for the risk measurement of the credit portfolio introduced with Basel II do not apply. The leverage ratio is limited by a simple comparison of tier 1 capital and the total assets, in which this ratio must be at least 4%. Small banks are exempted from disclosure requirements. The example of small banks shows that the rules for solvency, leverage ratio and disclosure are stable, simple and implemented with conservative calibration.

The next largest group of non-advanced banks—community banks with total assets below $15 billion—unlike small banks, must calculate the risk measurement of their loan portfolio (with the exception of residential mortgage loans) using the Basel II standard approach and must also meet CET 1 ≥ 4.5% from Basel III. The simplified calculation of the leverage ratio and the exemption from the disclosure requirement is similar to those of small banks. The set of rules for community banks remains simple and robust, but already includes risk measurement content from Basel II as well as Basel III capital requirements.

Compared to the community banks, the medium banks as the largest non-advanced group of institutions, apply risk measurement according to the standard approach of Basel II to their entire loan portfolio, i.e. also for residential real estate. While the calculation of the leverage ratio is simplified in much the same way as in small and community banks, medium banks, who make up the largest group of non-advanced banks, are obliged to disclose.

BankingHub-Newsletter

Analyses, articles and interviews about trends & innovation in banking delivered right to your inbox every 2-3 weeks

"(Required)" indicates required fields

Advanced banks must increasingly apply the requirements of Basel III. Large banks—i.e. institutions with total assets below $700 billion—must meet a CET 1 of at least 4.5% for solvency as well as both capital preservation and countercyclical capital buffers. Moreover, they have to calculate the risk measurement via internal models taking into account the floor. In comparison to non-advanced banks, the calculation of the leverage ratio according to Basel III is used for large banks, i.e. the ratio of the core capital to the leverage exposure must be at least 3%. Likewise, large banks are obliged to disclose.

In addition to the same requirements of the large banks, the group of institutions of the advanced banks with more than $700 billion of total assets—the so-called G-SIBs or global systemically important banks[7]—must additionally meet the G-SIB buffer between 1.0% and 2.5% as well as stricter requirements for the leverage ratio: the leverage ratio for G-SIBs must be at least 5.0%.

“Only 15 institutions in the US fully apply Basel III.”

As a consequence of the two-tiered regulation approach and the application of the minimum requirements of Basel III based on the size and systemic importance of an institution, only 15 institutions in the USA must fully apply and comply with Basel III. In comparison: with the translation of Basel III into the European Single Rule Book of the CRR/CRD IV, the Basel Guidelines must be fully applied and complied with by all 1,888 credit institutions and savings banks[8] in Germany, irrespective of their international, national, systemic or non-systemic classification.

User group of the simplified rules

In addition to the question of the systematic design of the small banking box via a detailed or two-tiered regulation approach, the user group must be defined in the course of developing the small banking box.

To derive the user group of the small banking box, the Bundesbank proposes a combination of total assets less than three billion EUR and other qualitative criteria (e.g. settlement of an institution in the insolvency proceedings, no noteworthy capital market or cross-border activities, small trading and derivatives book, no application of internal models)[9]. This proposal is based on the idea that institutions with riskier business models should be excluded from the user group of the small banking box from the outset. This combination is intended to exclude systemic risks that could arise from the interconnectedness of many small institutions (“too many to fail”).

BaFin discusses the use of existing distinctions and proposes a three-stage regulation approach. For example, BaFin believes that institutions that are below the threshold for potentially systemically important institutions (PSI) could benefit from simplifications. Non-PSI institutions could, in turn, be divided into large and small institutions.[10]

Recent signals from BaFin, Bundesbank and the Association of German Banks (Bankenverband) are creating a tailwind for the discussion about proportionality. A united German stance can solve the heterogeneous opinion formation in the EU and relieve pressure on German institutions.

Small banking box in line with the level playing field

The procedural relief in banking regulation which has for many years been demanded by medium-sized institutions, is comprehensible insofar as the regulatory objectives (depositor and system protection) can also be achieved with lower requirements. This applies in particular to their simple and low-risk business models focusing on the lending business in medium-sized enterprises (SME) and residential real estate financing. The aim of strengthening the idea of proportionality must therefore be to provide adequate relief without weakening the core regulatory objectives (including the Basel III capital and liquidity requirements) as a constraint. These reliefs can be realized via the aforementioned detail-oriented approach or the two-tiered approach.

As part of the current discussion, a solution has to be developed by the banking sector and the supervisory authorities—the solution must on the one hand achieve the central goal of relieving the burden of medium-sized institutions, while on the other hand also preserving the level playing field for large banks. The current revision of the CRR / CRD provides a very good opportunity to bring proportionality proposals into the political process.[11] The proposals made so far in this context were introduced in line with the detailed regulation approach. However, in light of the described benefits of a two-tiered approach, all stakeholders should consider whether the objectives for institutions and banking supervision could possibly be achieved more efficiently with such a regulation approach. The creation of a small banking box in the detail-oriented regulation approach carries the risk of cherry picking. In addition, the institutions involved are required to implement every new initiative in the dynamic regulatory environment—albeit in a simplified form. Topic-specific facilitations will continue to be integrated into existing legislation and may even increase complexity. In addition, the two-tiered regulation approach represents the opportunity for a fresh start, since a set of rules can be completely redesigned in terms of content.

Independent regulation for medium-sized institutions would be much more static if the regulatory goals were achieved and would significantly reduce the change-the-bank (CtB)[12] costs in the institutions. At the same time, it would be easier for bank supervisors to react promptly and consensually to developments in the business models of large international institutions, as discussions about whether or not to consider simple business models become redundant.

Last but not least, large institutions should also contribute to the preservation of the level playing field by joining in the discussion on the design of a small banking box.

Literature

BaFin (2016): In Deutschland identifizierte anderweitig systemrelevante Institute und deren Kapitalpuffer, Bonn/Frankfurt a.M.

Bayerischer Bankenverband (2016): Vorschläge für Erleichterungen für kleine und mittlere Banken in Regulierungs- und Aufsichtsthemen, zugleich Beitrag zur Diskussion zur „Small Banking Box“, München.

BCBS (2013): Global systemically important banks: updated assessment methodology and the higher loss absorbency requirement, Basel.

Bundesbank (2017): Bankstellenstatistik per 31.12.2016, Frankfurt.

Bundesverband der Deutschen Volksbanken und Raiffeisenbanken (2016): Qualität der Bankenregulierung verbessern – Kollateralschäden vermeiden, Berlin.

Dombret, Andreas (2017): Auf dem Weg zu mehr Verhältnismäßigkeit in der Regulierung?, Vorschlag für eine Small Banking Box, Rede v. 29.08.2017, Bonn.

Mussler, Werner (2016): Schäuble will weniger Regulierung für kleine Banken, FAZ, 14.04.2016.

Peters, Hans-Walther (2017): Kleine Banken entlasten, Börsenzeitung, 05.05.2017.

Röseler, Raimund (2017): Eigenmittel bei Banken – Das Thema Proportionalität drängt, BaFin Journal 04/2017, pp. 31-34.