|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

Tax authorities are facing new challenges

The rise of digital assets in recent years presents tax authorities with new challenges. In particular, the underlying distributed ledger technology (DLT) pays no attention to national borders. As a result, tax authorities struggle with a lack of transparency regarding capital income from crypto-asset trading. According to the regulators, this may facilitate tax evasion and tax fraud, the prevention of which requires close international cooperation.

To close any digital assets-related tax loopholes, the OECD has updated the Common Reporting Standard (CRS), turning it into a basis for the global automatic exchange of financial information on crypto-assets. Moreover, the OECD published the Crypto-Asset Reporting Framework (CARF), which entails global standardized due diligence and reporting obligations for crypto-asset service providers. 48 countries have signed a cross-national OECD declaration and thus committed themselves to implementing the CRS amendment and CARF by January 2027.[2] The European Union is implementing the new regulations as part of the Directive on Administrative Cooperation 8 (DAC 8), which – as all EU directives – requires transposition into national law by the individual EU member states.[3] Similar legislative proposals are expected for Switzerland and Liechtenstein in mid-2024.

Implementation timeline

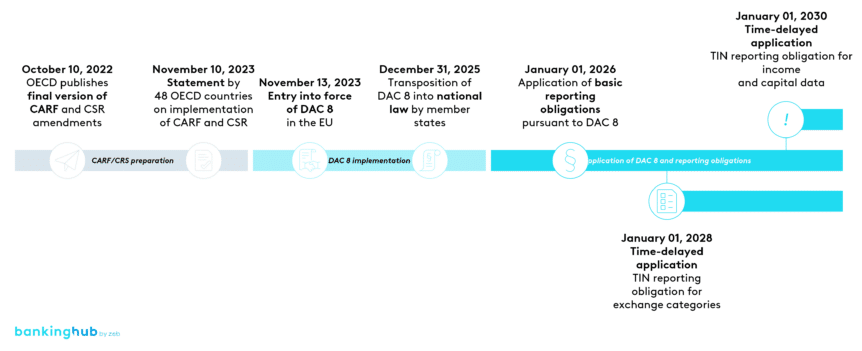

Having been mandated by the G20 countries, the OECD adopted the final version of CARF and the CRS amendment on October 10, 2022. On November 10, 2023, 48 OECD member states published a joint statement, committing themselves to implementing CARF and the CRS amendment. They also confirmed their intention to implement the regulations by the beginning of 2027. The European Union implemented CARF/CRS in the form of DAC 8, which came into force on November 13, 2023. After transposition into national law, DAC 8 will be binding as of January 1, 2026.

Crypto transactions are to be reported in the year following the transaction, i.e. as the DAC 8 reporting obligations will come into force on January 1, 2026, reports will have to be submitted from January 1, 2027. TIN-related reporting obligations start a bit later than that, as the European Commission is planning to develop and publish a dedicated IT tool to forward TINs (tax identification numbers) and automate TIN checks.

From January 1, 2028, TIN data and other related information for various exchange categories will be collected and shared between the relevant authorities. These categories include advance cross-border rulings and advance pricing arrangements (DAC 3), country-specific reports (DAC 4) and reportable tax arrangements (DAC 6). Specifically for the reporting of TINs related to income and capital data that are subject to the automatic mandatory exchange of information (DAC 1), the deadline has been extended until January 1, 2030.

The Swiss Federal Department of Finance is preparing a consultation draft on the implementation of CARF and CRS that is supposed to be ready by the middle of the year. Liechtenstein envisages a similar timeframe. Due to DAC 8’s extraterritorial scope of application, Swiss and Liechtenstein crypto-asset service providers that execute transactions for EU citizens are equally affected by this EU legislation. It can therefore be assumed that the legislative proposals for the implementation of CARF and CRS for Switzerland and Liechtenstein will be based on DAC 8.

BankingHub-Newsletter

Analyses, articles and interviews about trends & innovation in banking delivered right to your inbox every 2-3 weeks

"(Required)" indicates required fields

EU implementation: DAC 8

The European DAC 8 aims to create tax transparency regarding crypto assets and thus represents the first step toward a harmonized EU-wide tax framework. Assets that are subject to reporting obligations pursuant to DAC 8 include all crypto-assets used for payment and investment purposes, i.e. specifically cryptocurrencies, stablecoins including e-money and CBDCs, and in some cases also NFTs. Direct and indirect investments in digital assets, e.g. in the form of derivatives or similar investment vehicles, are also included.

Reporting providers according to the Markets in Crypto-Assets Regulation (MiCAR) are crypto-asset service providers (CASPs), i.e. crypto service providers that execute crypto transactions, including crypto exchanges, crypto custodians, crypto ATMs, crypto brokers, as well as so-called crypto-asset operators (CAOs).

According to MiCAR, CASPs must be registered in a member state, while CAOs must register as providers in a member state outside the MiCAR scope of application. Reportable users include all residents of the EU who are customers of a CASP or CAO, regardless of where the reporting provider is registered or the amount of the transaction.

The EU adopts the following measures as part of DAC 8:

- Self-disclosure by affected users

- Automatic exchange of information and reporting obligations regarding crypto transactions incl. tax identification number

- Special provisions: Advance tax rulings for wealthy individuals

- Determination of sanctions at the national level

As a first step, the institutions concerned must obtain information from their customers as part of their due diligence and forward it to the relevant authorities.

In the next step, DAC 8 mandates either a reporting obligation at the transaction level or that the information be automatically exchanged both domestically and across borders. The transaction data to be transmitted includes, in an aggregated form, the type of transaction, e.g. fiat–crypto or crypto–crypto, the number of units transferred, the fair value and personal data including the tax identification number. The latter plays a key role in the context of DAC 8, as it allows the relevant authorities to identify taxable persons and to be able to correctly assess and subsequently levy taxes. The reporting obligations also apply to the recipient of the transaction.

In addition, DAC 8 mandates the exchange of information regarding advance tax rulings for wealthy individuals, specifically for taxpayers with an annual aggregate transaction volume of more than EUR 1.5 million. In Germany, for example, advance rulings are already common practice for tax offices to provide information on future tax matters, but in some EU member states, there are no advance tax rulings to date.

The EU member states were unable to agree on a uniform approach to sanctions. Therefore, no sanctions are specified in DAC 8. Those have to be implemented individually by each affected member state. In any case, the sanctions ought to be “effective, proportionate and dissuasive”. In addition, DAC 8 mandates CASPs to prevent users from carrying out further crypto transactions if the required information has not been provided within 60 days and after two follow-up requests.

While MiCAR regulates access for crypto-assets to the markets in the EU, it does not provide any framework for tax authorities to levy taxes on crypto assets. Therefore, although DAC 8 is based on the same definitions as MiCAR, there are fundamental differences, for example with regard to reporting and due diligence obligations as well as the scope of application. DAC 8 has a so-called extraterritorial scope of application. This means that the directive applies to all crypto-asset service providers that provide services to EU citizens, regardless of whether they fall within the scope of MiCAR. This affects in particular CASPs based in Switzerland and Liechtenstein operating in the EU.

Recommendations for financial institutions

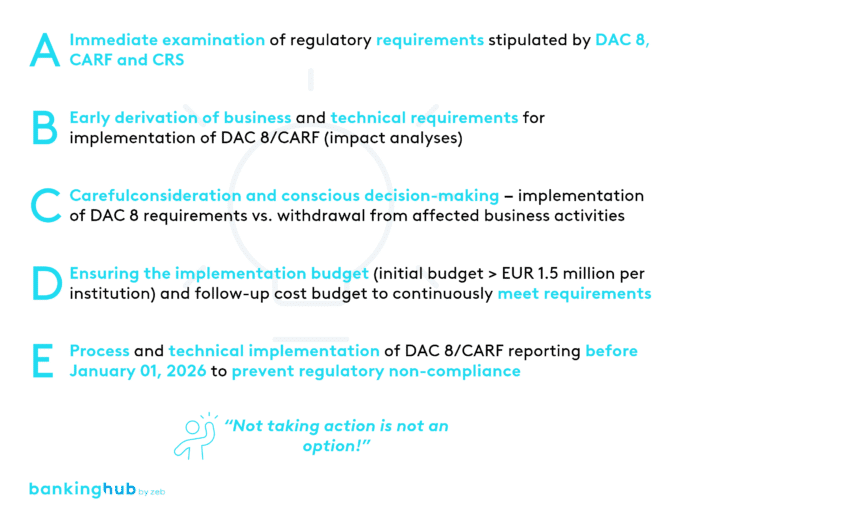

- To ensure that the timeline complies with the regulations, crypto-asset service providers or financial institutions with crypto offerings should start dealing with issues pertaining to crypto-assets and taxes in the context of CRS, CARF and DAC 8 as early as possible. This will allow them to determine the degree to which their own business activities are affected by the respective regulations in good time.

- Institutions that follow this advice will be able to carry out impact analyses without any time pressure and to derive appropriate technical and business requirements based on the new regulations at an early stage.

- This will give them leeway to carefully consider whether they want to meet the requirements stipulated by CRS/CARF/DAC 8, or whether they want to withdraw from the respective business sector / no longer provide the affected service.

- The implementation of DAC 8 comes with considerable implementation costs for crypto-asset service providers, which the European Commission estimates at around EUR 1.5–2.0 million per institution.[4] On top of that, they should expect running costs of EUR 150,000 per year. These costs must be taken into account in budget planning for the coming years to continously meet any newly arising requirements. Although traditional banks will have to deal with high implementation costs, they are used to high reporting requirements. By contrast, many crypto start-ups will have to venture into uncharted territory and invest large sums of money to meet the increased compliance requirements. DAC 8 might thus inhibit their innovative power in the future.

- Especially process and technical implementation should be completed early on in order to avoid regulatory non-compliance at the time of full adoption. This applies in particular to processes relating to customer onboarding and the associated communication as well as general compliance and control processes, for example, to processes for preventing people who failed to provide a self-disclosure after multiple requests from initiating new transactions.