|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

|

LISTEN TO AUDIO VERSION:

|

Banking turmoil: banks underperform all other sectors in Q1 2023

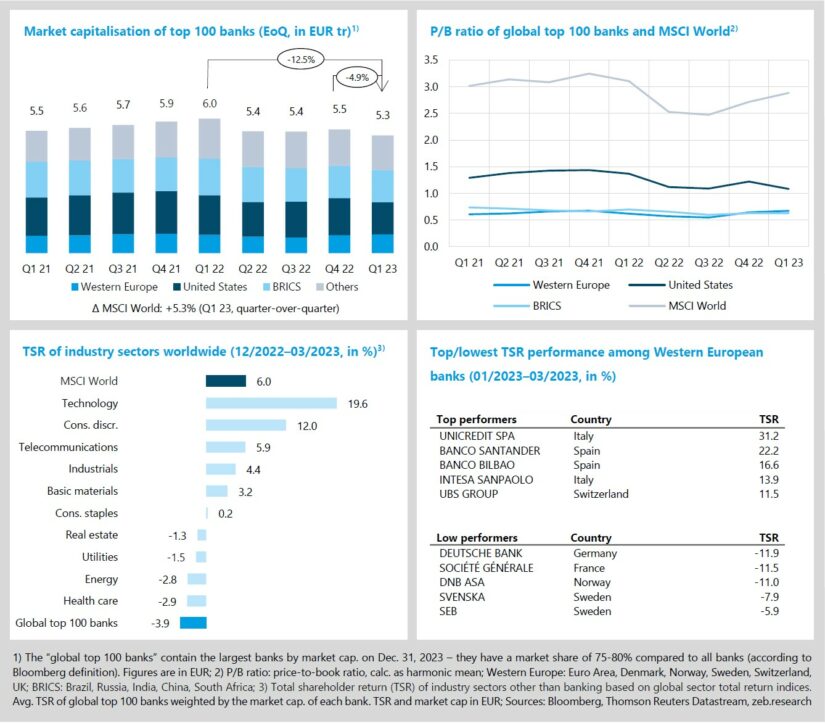

-3.9% QoQ TSR performance of global top 100 banks

- Turmoil in the banking market has led to banks underperforming all other sectors in Q1 23, with technology being the highest performer (+19.6% QoQ).

- U.S. banks were hit hardest by market turmoil (TSR -11.9% QoQ), while Western European banks (TSR +5.6% QoQ) lifted the global top 100 banks.

The collapse of SVB and CS in March 2023 was a main driver of capital market performance in Q1 23 and influenced market expectations, especially regarding future FED and ECB rate hikes – see chapter 3 for more details on the collapse of SVB and CS and the implications. Despite this, global capital markets overall had a good start (MSCI World TSR +6.0% QoQ, market cap. +5.3% QoQ). Performance of global top 100 banks (TSR -3.9% QoQ) and especially of U.S. banks (-11.9% QoQ) was negatively affected by the banking turmoil – Western European banks fared significantly better with a TSR performance of +5.6% QoQ (BRICS: -1.2% QoQ).

- In Q1 23, market capitalisation of global top 100 banks fell to EUR 5.3 tr (-4.9% QoQ), reaching its lowest level in more than two years. While S. banks exhibited the sharpest drop in market capitalisation since the outbreak of COVID-19 (-13.1% QoQ), Western European banks managed to continue their recovery from the previous quarter (Q1 23: +3.4% QoQ, Q4 22: +16.1% QoQ).

- On an industry sector basis, global top 100 banks were the worst performers in terms of TSR in Q1 23. Top performer was the technology sector (+19.6% QoQ), which profits greatly from cheap capital and thus benefited from falling yields and market expectations of weaker interest hikes by central banks in the future. In 2022, soaring interest rates had a strong negative impact on the sector (2022 TSR: -30.0% YoY).

- After reporting its highest quarterly profit for more than a decade (EUR 2.46 bn), UniCredit was the top performer of European banks in Q1 23 with a TSR of +31.2% QoQ. Despite its restructuring success and excellent TSR performance in the previous quarter (Q4 22: +41.5% QoQ), Deutsche Bank suffered from the high level of uncertainty surrounding the demise of SVB and CS and ranked last among Western European banks (-11.9% QoQ).

Erratic markets and high inflation put central banks in a dilemma

-0.1% YoY real GDP growth in Q1 2023 in Germany

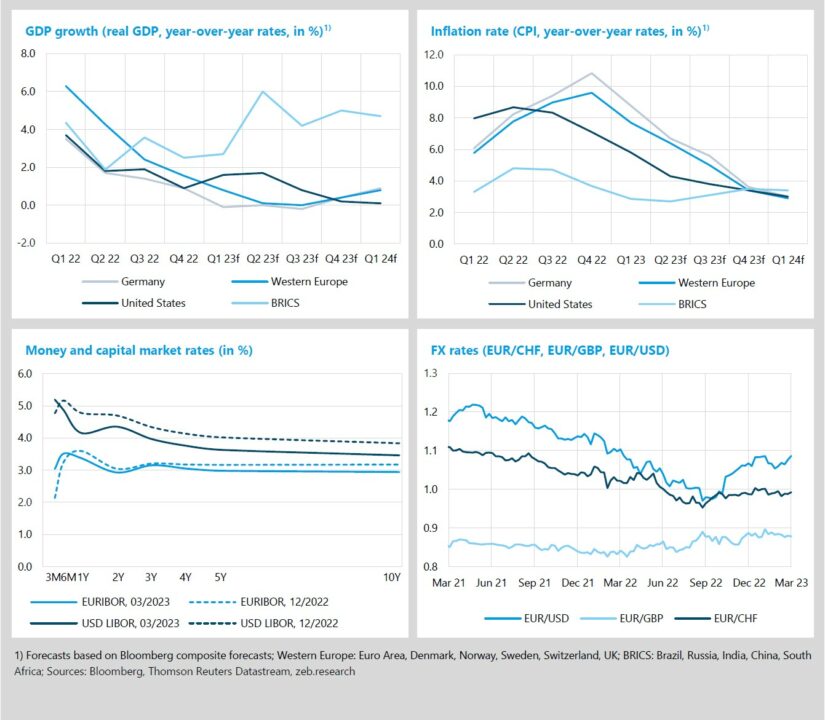

- Following improved GDP forecasts, Germany and Western Europe are now expected to avoid a technical recession in 2023.

- After peaking rates in Q4 22, inflation rates in Germany (8.8% YoY) and Western Europe (7.7% YoY) declined in Q1 23 but are still way above target levels.

Following slightly improved GDP forecasts, both Germany and Western Europe are now expected to avoid a technical recession in 2023. Hopes for a timely economic recovery are further fuelled by the prospect of an imminent end to interest rate hikes. The demise of SVB and CS and the subsequent banking turmoil highlighted the threat posed by rapidly rising interest rates. The resulting pressure for less restrictive monetary policy puts central banks in a dilemma. Inflation fell in Germany (8.8% YoY) and Western Europe (7.7% YoY) in Q1 23 but remains unacceptably high. The recent rebound in the EUR/USD FX rate to 1.09 in Q1 23 reflects market expectations that the FED may be less hawkish than the ECB going forward.

- Compared with previous GDP forecasts, the trough following the rapid interest rate hikes is expected to be less pronounced overall and to shift to Q3 23 for Germany (real GDP growth of -0.2% YoY) and Western Europe (+0.0% YoY). For the US, Q3 23 is expected to herald a period of economic stagnation until mid-24 with GDP growth rates below 1%. BRICS are expected to return to GDP growth rates above 4%.

- After peaking in Q4 22, inflation in Germany and Western Europe declined somewhat in Q1 23 (8.8% YoY and 7.7% YoY, respectively) and – similar to the U.S. – is expected to settle at around 3% early next year.

- Again, the S. yield curve has inverted further with negative spreads of -89bp and -173bp for 10Y-3M and 10Y-2Y, respectively, while the euro area yield curve is now virtually flat (10Y-3M: -10bp, 10Y-2Y: +1bp). Market expectations for the May meetings point to +25bp hikes by both the FED and the ECB. Based on current market expectations, the May FED hike could well be the last one.

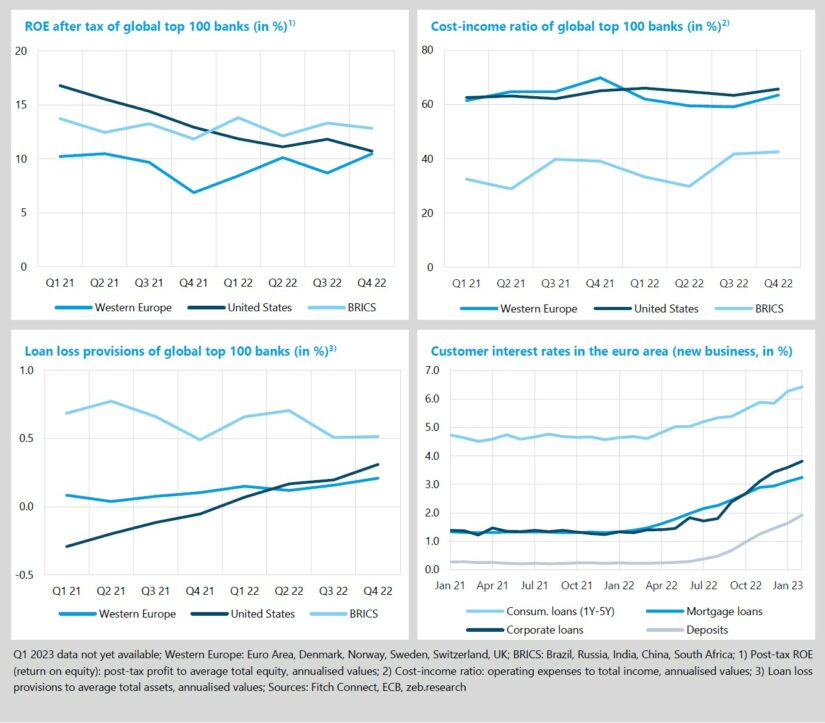

In Q4 22, Western European banks were again able to increase their profitability to over 10% with +3.6%p YoY and +1.8%p QoQ. By contrast, U.S. banks suffered a YoY (-2.2%p) and QoQ (-1.1%p) decline in their profitability and are now as close to Western European banks in terms of profitability as they last were in Q1 14. Loan loss provisions at U.S. banks rose again by +11bp QoQ, while Western European banks saw only a modest increase (+5 bp QoQ) and BRICS banks’ levels remained almost flat. Looking back at 2022, higher yields and the return of profitable deposit-taking (see zeb.market.flash Issue 42) have clearly benefited Western European banks more, while risks and provisioning have so far been more pronounced at U.S. banks.

- Western European banks improved their cost-income ratio (CIR) by 6.4%p YoY, driven by a slight decrease in costs (-1.3% YoY) despite very high inflation rates and a solid increase in revenues (+8.7% YoY). S. and BRICS banks both saw their CIRs increase by 0.7%p and 3.5%p, respectively – significantly higher revenues (U.S. banks: +15.1% YoY, BRICS banks: +21.7% YoY) could not offset the even stronger increase in total costs (+16.3% and +32.5%).

- Given the turmoil surrounding the SVB case and the pessimistic U.S. GDP forecast for the coming quarters, the continued rise in U.S. banks’ loan loss provisions in Q4 22 (+11 bp QoQ) is not surprising. Similarly, the sideways trend in BRICS banks’ loan loss provisions reflects their already comparatively high provisioning levels combined with a more favourable economic outlook.

- As the ECB continued to raise interest rates, customer interest rates also continued to rise. From November 2022 to February 2023, corporate loans and fixed deposits increased most strongly, by 70bp and 67bp respectively. The substantial increase in corporate loans is driven by higher funding costs, but also by higher risk costs. On the deposit side, the main driver was the continued intensification of competition.

Special topic – banking crisis 2.0 and its regulatory implications

- The collapse of Silicon Valley Bank (SVB) and Credit Suisse (CS) in March 2023 caused significant turmoil in global banking and beyond.

- Given the widespread fear of contagion in the banking sector, we address three fundamental questions: 1) Do the failures of SVB and CS point to a larger systematic problem? 2) Do the banks’ KPIs indicate another global banking crisis? 3) Do the cases of SVB and CS call for a further tightening of regulation?

The collapses of Silicon Valley Bank (SVB) and Credit Suisse (CS) within ten days in March marked the beginning of turmoil in global banking. While SVB was considered a mid-size bank by U.S. standards with total assets of USD 209 bn, CS was the second (twenty-fourth) largest bank in Switzerland (Europe) in Q4 22 with total assets of EUR 513 bn. Given the widespread fear of contagion, three fundamental questions arise for the banking world: First, do the SVB and CS failures point in the same direction, suggesting a major systematic problem rooted in the banking sector? Second, do banks’ KPIs indicate yet another global banking crisis? And third, do the SVB and CS cases compel a further tightening of the European regulatory framework?

The collapse of SVB is an example of poor asset/liability and interest rate risk management paired with a bank run. SVB had a loan-to-deposit ratio of only 43% by the end of 2022 (vs. the 50 largest European banks by assets: ~100%) and was thus highly invested in long-term (~10 years vs. ~2 years), secure, but low-yielding government bonds (own investments to total assets: 55% vs. ~10%). Depositors were mainly tech investors and start-ups with deposits >250.000 USD (i.e., deposits exceeding the FDIC insured amount). With the FED’s interest rate hikes, the days of cheap refinancing came to an end, and start-ups fell back on their cash reserves. This ultimately led to a widespread withdrawal of funds forcing SVB to sell bonds at sharply fallen market value and realize very high losses. The SVB case challenges the comparatively lax supervision of mid-size and small banks in the U.S. as there is a regulatory gap in terms of liquidity and interest rate risks for these banks which does not exist for the European market.

The demise of CS resulted from poor corporate governance causing repeated scandals and investors and customers to lose their confidence in the bank. After the financial crisis of 2008, CS stuck to its old business model and risk culture, provoking various reputation-damaging affairs such as the Archegos and Greensill cases. Thus, against the overall trend in the banking market, the systemically important bank with strong international ties had to report heavy losses in 2021 and 2022. The turn-around strategy presented in October 2022 failed to convince the market and was unable to stop the already significant outflow of customer funds. Despite liquidity support and special loans, the Swiss National Bank (SNB) was unable to put a lasting stop to CS’s confidence crisis and in the end opted for a takeover by UBS. This step was also undertaken since the SNB was pressured by foreign (esp. U.S.) authorities to intervene, due to CS being highly connected internationally, being very reliant especially on USD swaps and the authorities fearing a possibly devastating chain reaction in global markets.

Taking a theoretical position, a bank fails when it can no longer pay its debts to creditors as they fall due. This happens when the bank faces severe solvency or liquidity problems. Both SVB and CS collapsed because of exacerbated liquidity issues, yet this is where the similarities end. The SVB case illustrates a rather classic (yet incredibly negligent) bank failure following insufficient risk management. Conversely, CS failed because of its persistently poor corporate governance, causing various scandals and eventually the loss of confidence amongst investors and customers. Therefore, both bank failures have entirely different origins and by no means point collectively towards specific systematic deficits in the global banking sector.

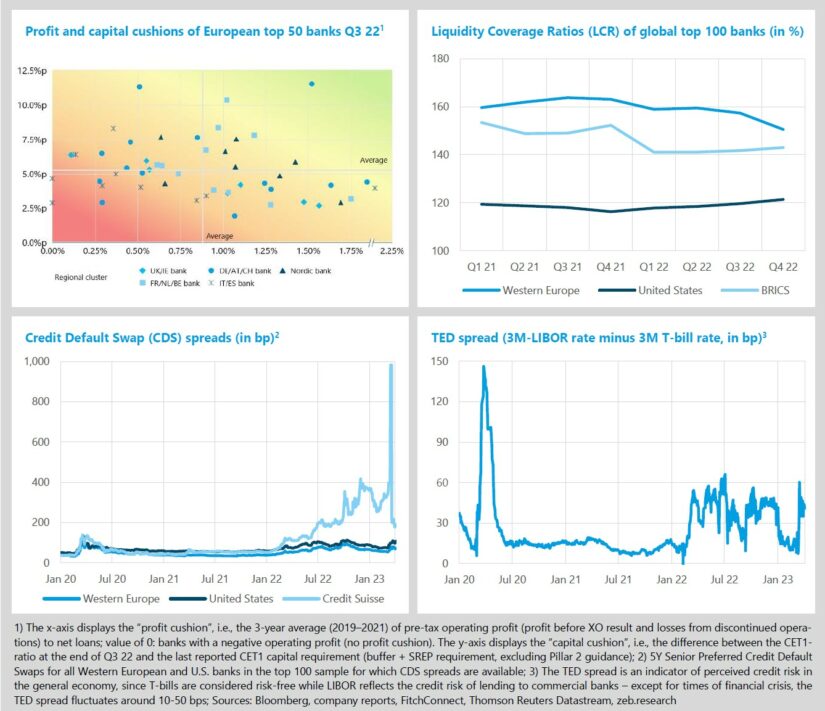

Turning to the second question – do banks’ KPIs indicate yet another global banking crisis? – the figures below show four views and indicators with relevance for the current state of the banking sector. At the end of Q3 22, the “profit cushion” (tolerable additional credit losses as the first safety rope) and the “capital cushion” (CET1 ratio – capital requirements as the second safety rope) among European top 50 banks were by and large sufficient to make up for possibly deteriorating assets and subsequent losses. Despite the slight recent improvements in profitability, the “profit cushion” – while far away from crisis levels – remains a key issue for European banks.

The liquidity coverage ratio (LCR) is a regulatory ratio to assess short-term liquidity risks of credit institutions. Looking at the regional averages of global top 100 banks, LCRs lie persistently above the 100% threshold, with Western European (U.S.) banks reporting the highest (lowest) LCRs. The predictive power of LCR figures for a liquidity-based bank failure, however, is limited. CS had an LCR of ~150% when it was acquired by UBS. For a bank the size of SVB, there are no regulatory LCR constraints in the US, yet the bank would also have reached an LCR of ~150% by the end of 2022.

CDS spreads are an indicator for market confidence in banks. CDS spreads for Western European and U.S. banks have risen modestly since March but are still below the highs seen after the outbreak of COVID-19 in 2020 and the major interest rate hikes in 2022. While CDS spreads are traded on relatively illiquid markets, are the subject of speculation and can therefore be very volatile, the persistent decoupling of Credit Suisse’s CDS spreads from the average of Western European banks starting in March 2022 was a clear warning sign.

The TED spread is an indicator of the perceived credit risk in the general U.S. economy as an increase is a sign that lenders believe the risk of default on interbank loans is growing. Except for times of financial crises, it usually remains within the range of 10 and 50 bps. While the interest hikes of the FED led to a higher TED spread and the failures of SVB and CS to a small spike, it generally remained significantly below COVID-19 peak levels. Overall, indicators do not suggest an imminent threat to the banking world. However, the CS and SVB cases have once again shown that bank failures do not necessarily give much advance notice.

So, do the SVB and CS cases compel a further tightening of the European regulatory framework? Government involvement in the rescue of two failing banks within a short period of time naturally triggers public calls for a stricter regulatory framework. Considering the SVB case, the failure of European banks due to interest rate and liquidity risks is currently unlikely. However, considering the current predictive power of liquidity figures like the LCR, liquidity risks are worth further consideration. It once again became clear that banks should have a clear and well-founded strategy around their funding mix and avoid potential cluster risks.

The CS failure raises questions about regulatory practices regarding bank governance – in case of persistently bad governance, there are calls for the supervisory board and more active supervisory authorities. A permanent dialogue, especially on top seniority level, and more context thinking by authorities is paramount in preventing another CS case. Furthermore, as seen with CS, a review of the political feasibility and practicality of “too-big-to-fail” regulation for banks is necessary. The ECB and BoE initially did a good job by emphasizing that they certainly would adhere to their own bank recovery and resolution mechanisms – and not, for example, disadvantage AT1 bond holders compared to shareholders, as done by Swiss authorities. This communication strategy immediately helped to calm the financial market.

In the end, the collapses of SVB and CS do not automatically compel a further tightening of the European regulatory framework. However, looking for example at the “too-big-to-fail” problem, or the further existing doom loop between banks and sovereigns, there is still a lot to do for European regulatory authorities.