|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

A look at the current situation of universal banks shows a mixed picture. On the one hand, especially the low post-tax return on equity of only 2.3% in 2013 is a reason for concern. On the other hand, institutions definitely improved their capital ratios, e.g. Tier 1, CET1 and the leverage ratio, by adding new capital and reducing risk-weighted assets over the last years, meaning that they are currently in a relatively good position. Nevertheless, based on a baseline simulation, the current mediocre situation will become more and more difficult until 2018.

In our baseline scenario (figure 2), we project a decline of the net interest income by approx. 12% until 2018, due to depressed yield curves. As expected, this decline will be slightly lower for universal banks than for retail banks. As other income components cannot offset the interest income deterioration, total profits of universal banks will also decline, resulting in an average post-tax return on equity of only 1.4% in 2018. This means that the currently already low profitability will shrink even further—a similar situation to that of international retail banks. Banking’s costs of equity or double digit RoE figures will not even nearly be reached.

Constantly poor profits lead to continuously low retained earnings and therefore limit the urgently needed generation of capital significantly. The effects on the capitalization of universal banks are tremendous, because the fully loaded Basel III CET1 ratio will only barely be met in 2018 (based on an assumed minimum CET1 ratio of 9%). Aside from low capital generation, the main reasons for the capital shortage are capital deductions for goodwill, holdings and deferred taxes—although many universal banks have already included and considered a certain share of deductions—and the effects from higher capital requirements for some typical universal banking products, e.g. derivatives. In this baseline scenario, future growth is hardly possible without additional capital, due to the already low CET1 ratio. Other regulatory requirements, the leverage ratio and the LCR, are mostly in line, although some definitions and hurdles have not been fully fixed yet.

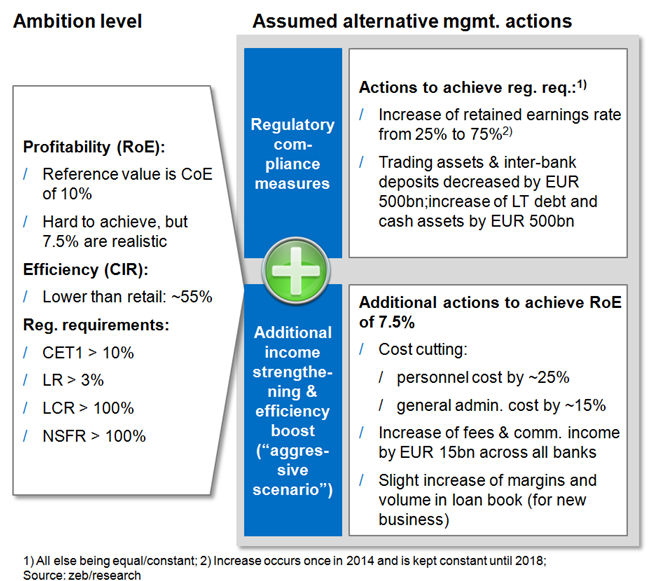

How can universal banks overcome this situation? In the following, we will present two management reaction scenarios: The first scenario—the so called regulatory scenario—considers measures that will lift universal banks’ regulatory ratios above the ambition levels required by investors and capital markets. The second, aggressive scenario includes additional management actions to achieve higher profitability and efficiency. See figure 3 for more details on the suggested actions.

The regulatory scenario requires a significant increase of the retained earnings rate to improve capital generation and changes in the asset mix with a view to liquidity ratio improvements. However, the below calculations (figure 4) clearly show that while these suggested measures help banks to meet regulatory requirements, they also lead to a further decrease of profitability (even below baseline figures). To achieve a reasonable return on equity, substantial additional actions are required, including substantial cost-cutting programs, improving sales activities in combination with a shift of income sources to offset the interest income decrease, and a loan book expansion due to relatively high margins.

A key part of the two scenarios is the optimization of the asset and funding structure. By focusing on stable customer funds and assets with higher margins, the negative effects of higher regulatory capital requirements for securities and derivatives can be alleviated, helping banks to meet capital and regulatory requirements. But even with fundamental concerted action of universal banks, they will not achieve a profitability level of more than approx. 7.6% in 2018—let alone the double digit returns required for the capital market. Only cutting personnel expenses by 25% and administrative costs by 15% until 2018 will not be sufficient in order to achieve a satisfying return on equity. Additional other measures will be necessary, which underlines how difficult the situation is for European universal banks. Business model optimizations and aggressive cost management will remain necessary for this bank cluster.

Based on these findings, the fight for capital and de-risking among universal banks will continue over the upcoming years. The leverage ratio will become a problem in some cases, especially due to exhausted netting opportunities. Stable liquidity has to be considered as a further aspect in capital and resource planning. At the operational level, the correlation between the low yield curve and declining total profits necessitates cost reductions. The universal banking business model has to be streamlined with particular focus on personnel cost drivers and optimizing the business portfolio. A search for alternative income sources is necessary. However, the ability of universal banks to use different business models within one institution is a strong opportunity for improving and sustaining profits and, in consequence, shareholder value.

Industry impacts are inevitable. Universal banks can no longer afford a simple “convenience store” attitude, unless banks find ways to realize significant economies of scale and/or cross-sales. Opportunities for each business model within an institution have to be identified (e.g. re-adjusting B/S composition, loan book, individual improvement of cost base, etc.). Two general strategic moves can be expected for universal banks: (1) identifying and facilitating overall synergies and collaboration models among business models (cross-sales) or (2) focusing on one particular model and becoming “best in class” (e.g. UBS, etc.). This means reducing unprofitable non-core business segments and focusing on selected core businesses.