|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

|

LISTEN TO AUDIO VERSION:

|

What medium-term interest rate scenarios are possible?

After the COVID-19 pandemic took the entire global economy hostage in 2020, 2021 was supposed to be the starting point for a broad global recovery. But things turned out differently. The beginning of the Russian war of aggression on Ukraine in February 2022 caused energy prices to soar – especially in Europe – and exacerbated long-standing global supply chain problems.

Exploding consumer prices force central banks to raise key interest rates

The result was a global inflation rate of 8.7% in 2022. In Germany, an inflation rate of 7.9% was temporarily expected, which would have meant the highest inflation since the introduction of the Deutsche Mark. An adjustment in the calculation on the part of the Federal Statistical Office led to the final figure of 6.9% – still, the highest inflation rate since the oil crisis in the early 1970s.

The rapid rise in inflation forced central banks around the world to act and resulted in no less rapid increases in key interest rates, aimed at curbing demand and thus price pressure. In terms of both pace and synchronization, these interest rate hikes were exceptional.

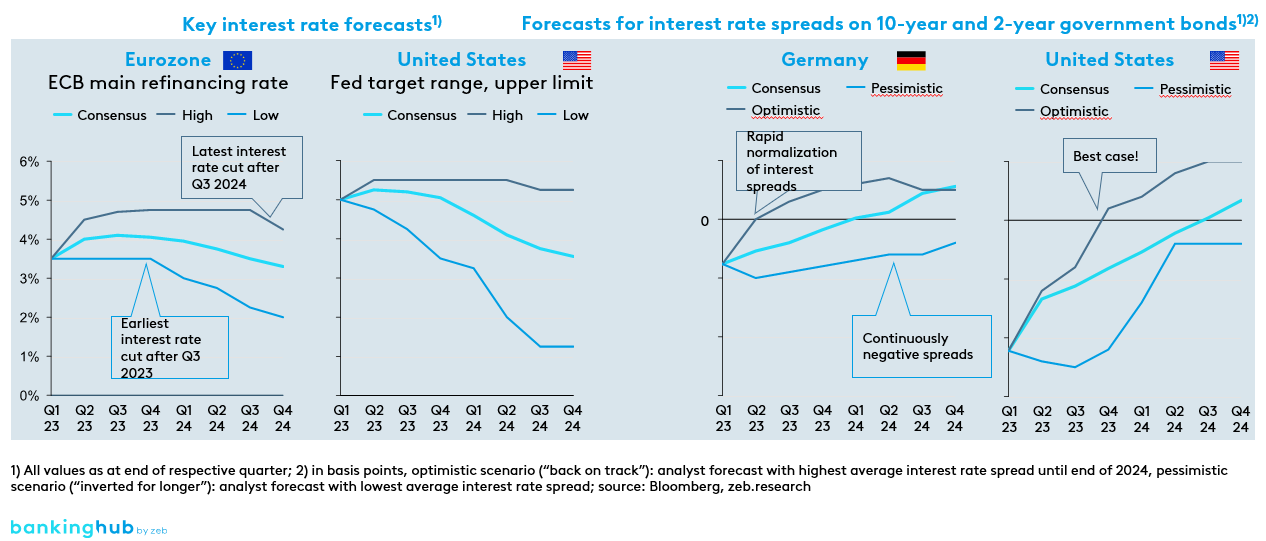

For example, the European Central Bank (ECB) and the U.S. Federal Reserve (Fed) raised their key interest rates by 375 bps and 500 bps, respectively, within no more than roughly a year. It is important to note that the ECB stuck to its original, very loose monetary policy for a long time. While key interest rates in the U.S. were first raised as early as March 16, 2022, the ECB did not react to the jump in inflation expectations until around four months later, on July 21, 2022.

Inverted interest rate spreads herald a cyclical downturn

Capital market interest rates, however, did not rise to the same extent as money market rates. Instead, an inversion of the yield curve occurred, which happens when the short end of the yield curve exceeds the long end. For example, the interest rate spread for ten-year and two-year German government bonds has been negative since November 2022, while the spread for U.S. government bonds has been negative since July 2022.

An inverted interest rate structure is generally taken as an indicator of a looming recession. By comparison, low long-term interest rates express the expectation of declining key rates in the future – a typical monetary policy in the course of a downturn. In view of these gloomy expectations, the currently forecasted declining but still positive growth rates in Western Europe in the coming years (2023: 0.4%, 2024: 1.2%) are still quite optimistic.

Two interest rate scenarios describe the current uncertainty

We distinguish between two possible scenarios for the medium-term yield curve. The “back on track” scenario describes the return to a normal, steep yield curve with long-term rates outpacing short-term rates. The “inverted for longer” scenario, however, predicts a continuously inverted interest rate structure in the medium term.

A normalized, steep yield curve can be expected in particular if the forecasted economic slump passes as mildly and quickly as possible, followed by a rapid and strong upswing. This expectation would be underpinned by a rapid decline in inflation, which would allow key interest rates to be lowered and likely push short-term interest rates below long-term rates. The recently improved supply chain situation, for example, points to this scenario.

A continued inversion of the yield curve is conceivable in the event of a stagnating GDP or an expected but postponed recession. Above all, persistently high inflation rates would make the “inverted for longer” scenario more likely. In this case, central banks would be forced to stick to a restrictive monetary policy, which would keep the short end of the interest rate structure high. The delayed recessionary effect of high central bank interest rates dampens the economic outlook and therefore makes the scenario of a persistently inverted yield curve more likely.

Key interest rates and interest rate spreads expected in the medium term

A look at current analyst forecasts highlights the high level of economic uncertainty prevailing at present. Consensus forecasts do not expect key interest rate cuts for virtually any currency area before the end of 2023. For the euro area, a key interest rate increase of 50 bps is expected, starting from the end of the first quarter of 2023. There is a significant range between the highest and lowest estimates. Both falling key interest rates (favoring the “back on track” scenario) and higher key interest rates (favoring the “inverted for longer” scenario) are conceivable. The forecasts also diverge significantly in terms of timing. For instance, the range for the earliest and latest decrease in key interest rates for the euro area is twelve months. For the U.S., these discrepancies are even greater.

In line with the key interest rate forecasts, the range of forecasts regarding interest rate spreads for ten-year and two-year government bonds is also wide. For both Germany and the U.S., the most pessimistic forecasts predict a negative spread until the end of 2024. By contrast, the most optimistic forecasts suggest a positive spread starting as early as 2023.

BankingHub-Newsletter

Analyses, articles and interviews about trends & innovation in banking delivered right to your inbox every 2-3 weeks

"(Required)" indicates required fields

What are the consequences for European banks?

The huge discrepancies between current interest rate forecasts combined with high macroeconomic uncertainty make a reliable prediction extremely difficult. Instead, the current message to European banks is to be prepared for both interest rate scenarios and to not categorically rule out either of them.

Interest rate scenarios have differing consequences for P&L positions of European banks

In the “back on track” scenario, the associated cuts in key interest rates would weigh on lending and deposit margins. Nonetheless, net interest income would benefit overall, as the normalized interest rate structure would raise expectations for the return of a positive contribution from maturity transformation and demand for loans would also pick up. At the same time, credit default risks would decline with decreasing interest rates. In addition, falling inflation in this scenario reduces the cost pressure currently faced by banks, at least to a certain degree. For non-interest income, however, no clear relationship can be established in any scenario. So overall, the “back on track” case would be good news for banks’ operating profits.

In the “inverted for longer” scenario, persistently high key interest rates would benefit banks’ margins, but net interest income would still suffer overall, as a continued negative contribution from maturity transformation and falling demand for loans are to be expected. The continuously high cost pressure in the wake of the high inflation associated with the scenario represents an additional burden for the operating result. Furthermore, the rising credit default risk would hit banks, putting significant pressure on the overall operating result due to several heterogeneous burdens.

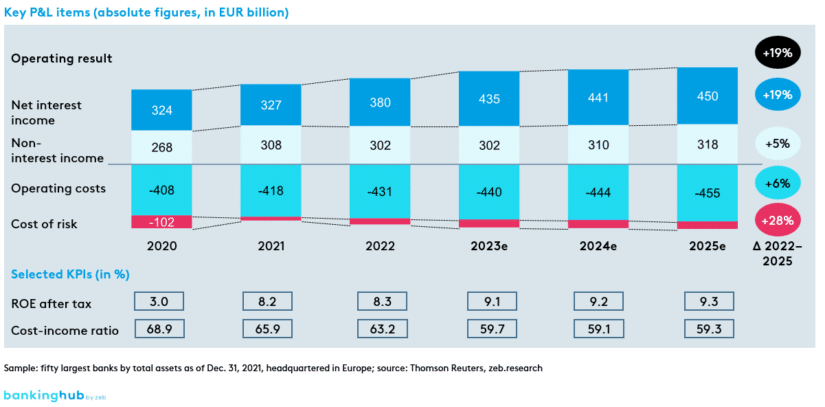

Analysts expect positive development of European top 50 banks in the coming years

Current analyst forecasts for core P&L items of European top 50 banks reflect the positive underlying sentiment associated with the rise in interest rates. Net interest income is expected to increase (+19% from 2022 to 2025) and cost of risk is expected to normalize (+28%). The analysts see banks in a position to cushion the impact of inflation on their costs (operating profit +19%). The key issue, however, is that a deterioration in the interest rate and economic environment would cause massive problems for banks. Despite the generally optimistic outlook, it is therefore necessary to subject possible future scenarios to a critical examination.

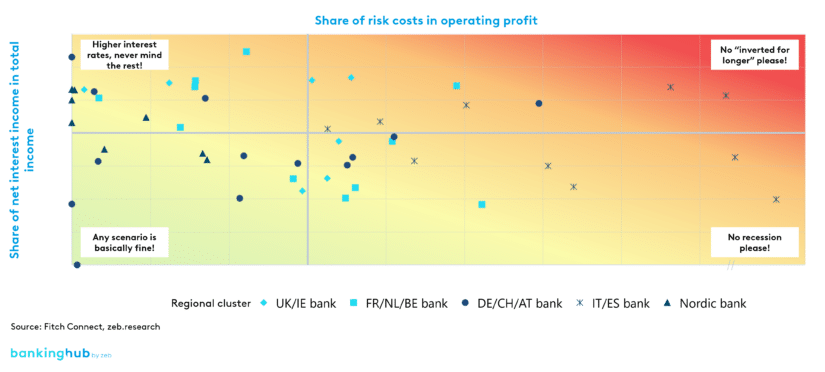

European banks would be affected in different ways by the “inverted for longer” scenario

Selected banks would be particularly affected by an ongoing inverted interest rate structure, as they are exposed in two critical dimensions. As shown in Figure 3, net interest income accounts for a large share of their total income (y-axis), while cost of risk in relation to operating income is particularly high (x-axis). By contrast, other major banks are less affected by the interest rate environment due to their high non-interest income. The impact of risk costs on operating profit also varies considerably. Many banks currently have a very low cost of risk.

What control levers do institutions have?

Overarching measures are needed to limit the risks of the interest rate turnaround and exploit earnings opportunities. Four fields of action are given here as examples.

- Customer business:The pricing of customer deposits, the structure of the deposit portfolio, and the optimization of price enforcement in the lending business naturally offer control levers. The key success factor is the dashboard for monitoring and managing deposit products and interest rate conditions.

- Treasury:The decisive factors are the realignment of the interest rate strategy / maturity transformation and the hedging of long-term fixed interest rates in new business, as well as the careful selection of necessary controlling instruments. The key success factor is to maximize the interest rate responsiveness of the entire asset side.

- RWA optimization and risk controlling:The implementation of short-term measures to optimize RWA and the reassessment of risk-bearing capacity make an important positive contribution. Additionally, ways to deal with high losses in market value in the interest area / options for compensation in other risk classes should be examined. The key success factor is the scenario-based optimization of risk allocation and risk-bearing capacity, i.e. creating “breathing space” for crises.

- Scenario capability:It is important to build scenario capability in all areas of the bank, especially with regard to key KPIs. At the same time, interfaces in management and customer business should be created and subsequent measures derived. The key success factor is the adoption of a resilient approach, i.e. “hope for the best, plan for the worst”.

Conclusion: “back on track or inverted for longer?”

Over the past twelve months, we have seen a rapid increase in key interest rates due to high inflation rates. In principle, the interest rate turnaround is good news for banks, as it promises a comeback of the “old world” including profitable deposit business and higher returns on equity.

However, the current inverted yield curve poses several potential risks. Although a “back on track” scenario in the near future is realistic, the macroeconomic environment remains unstable. Detailed discussions of the consequences and fields of action in the “inverted for longer” case are therefore well worth having.