|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

The need for carbon accounting

Climate neutrality means that on balance (= in net terms) no additional greenhouse gas (GHG)[1] is emitted into the atmosphere as a result of activities and/or investments. When evaluating the extent to which the economic activities financed by a financial institution are detrimental to the climate, the first question is whether the impact of these activities can be measured.

It is a process of recording and quantifying GHG emissions directly or indirectly associated with an entity. The Greenhouse Gas Protocol (GHG Protocol) distinguishes three “scopes” of emissions:

- Direct emissions (scope 1) are caused by the company itself, in particular through production.

- Indirect emissions also include those resulting from the generation of purchased and consumed energy such as electricity and (district) heating (scope 2),

- as well as emissions generated along the value chain (scope 3).

Emissions caused upstream in the value chain (e.g. during purchasing) are also referred to as upstream emissions. Downstream emissions are those generated for distribution, use and disposal at the end of the value chain.

The GHG Protocol distinguishes 15 categories of upstream and downstream scope 3 emissions. For financial institutions, emissions in category 15 “Investments” are particularly significant, as it includes financed emissions.

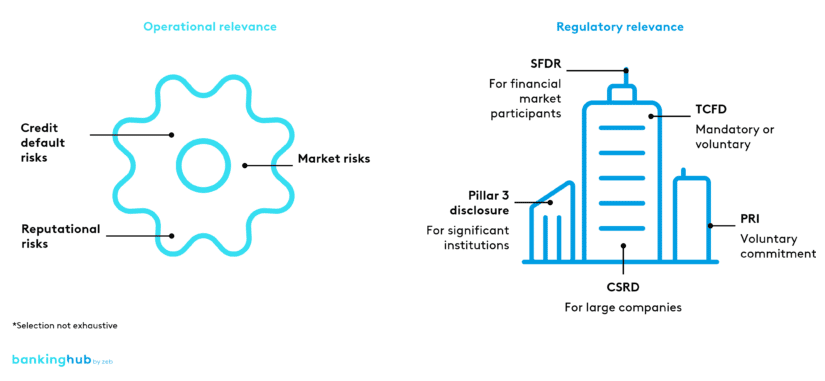

Operational and regulatory relevance of carbon accounting

Carbon accounting can be relevant for financial institutions for operational as well as regulatory reasons:

Operational reasons: Carbon accounting is significant mainly because of the additional financial climate risks as well as the potential reputational risks associated with GHG emissions. GHG emissions provide information about a company’s adverse contribution to climate change (inside-out view). In addition, metrics on GHG emissions can be used to draw conclusions about the potential financial impact on financial institutions, which can result primarily from transition climate risks (outside-in view):

- Transition climate risks: Changing demand patterns (e.g. reduced meat consumption) or regulatory decisions (e.g. driving bans on internal combustion engine vehicles) may reduce GHG-intensive business, or increases in the price of GHG emissions (e.g. through CO2 pricing) may make this type of business unprofitable. The quantification of transition risks can include total GHG emissions in absolute terms, GHG footprint or relative GHG intensity. Financial institutions are particularly affected if their portfolios consist of exposures to GHG-intensive companies. Specifically, transition risks can take the form of additional credit default risks or market risks:

- Credit default risks: Borrowers with high GHG intensity are most affected by climate-related political and economic change and face increased default risk. From the perspective of financial institutions, the resulting financial burdens from transition climate risks affect companies in the loan portfolio through both the probability of default (PD) and the loss given default (LGD).

- Market risks: If demand for GHG-intensive assets (e.g. fossil fuels) dwindles, there is a risk of investments becoming stranded assets, i.e. assets for which prices collapse due to lack of demand.

- Reputational risks: These arise when financial institutions are seen as paying little attention to sustainability due to the emissions associated with them or are associated with climate change and its impacts. GHG intensity can give stakeholders an idea of the extent to which sustainability issues are taken seriously by the financial institution. The impression of insufficient sustainability efforts can significantly damage reputation and cause problems for financial institutions, especially in the areas of new customer and staff acquisition.

Regulatory reasons: Regulatory relevance results from national or European requirements. In the EU, GHG metrics are already required under various regulations. The Disclosure Regulation (SFDR) requires financial market participants to disclose GHG emissions as part of what is generally referred to as adverse impacts on sustainability. Significant institutions will have to provide information on financed emissions in Pillar 3 disclosures from mid-2024 at the latest. According to the planned EU Sustainability Reporting Standards (ESRS) under the Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD), large companies will have to disclose direct and indirect GHG emissions in their non-financial reporting.

In addition, pressure to act may arise from voluntary commitments or international standards. The standards of the Task Force on Climate-Related Financial Disclosures (TCFD) require the reporting of various GHG emissions metrics. Although this is a private law initiative, the provision of information under the TCFD is already being made compulsory by some regulators. In Switzerland, large institutions are required to disclose based on the recommendations of the TCFD, and in the UK, similarly, the largest companies and financial institutions. Declarations of voluntary commitment such as the Principles for Responsible Investment (PRI) also make use of GHG metrics as key TCFD indicators.

From both a business and regulatory perspective, financed GHG metrics are thus key benchmarking and management metrics. As such, they can serve as a basis for financial institutions to set specific and measurable targets, plan actions to reduce emissions and disclose what progress they have made.

BankingHub-Newsletter

Analyses, articles and interviews about trends & innovation in banking delivered right to your inbox every 2-3 weeks

"(Required)" indicates required fields

Best practice approach in carbon accounting

The framework of the Partnership for Carbon Accounting Financials (PCAF) has developed into the leading standard for measuring financed greenhouse gas emissions. PCAF is a global network of financial institutions which aims to develop a harmonized approach to measuring and disclosing GHG emissions financed in the loan portfolio and in an institution’s own securities account. In its 2020 version, the PCAF standard covers the following asset classes:

- Listed equity and corporate bonds

- Business loans and unlisted equity

- Project finance

- Commercial real estate

- Mortgages

- Motor vehicle loans

GHG emissions generated in third-party securities accounts are not included herein. The PCAF standard is compatible with globally recognized standards and initiatives such as the GHG Protocol, the Climate Disclosure Project (CDP), and the TCFD standard.

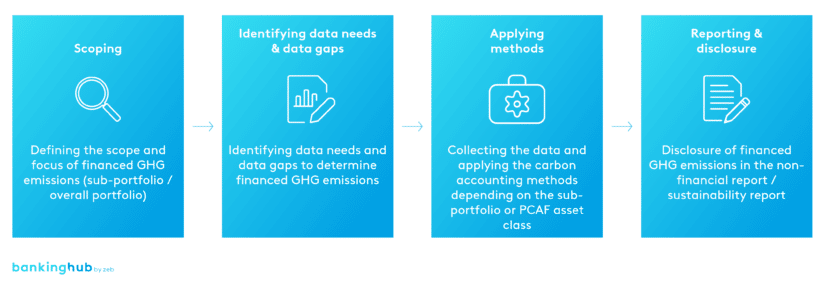

The approach under the PCAF standard consists of (1) scoping, (2) identification of data needs and data gaps, (3) application of methods, and (4) reporting and disclosure.

- Scoping: First, the scope or focus of the GHG emission calculation must be determined. GHG emissions do not have to be calculated at the overall portfolio level from the outset. Many financial institutions initially determine their financed GHG emissions for selected sub-portfolios or PCAF asset classes with high data availability and/or data quality. Nevertheless, for a holistic view, the aim should be to achieve the highest possible coverage of the overall portfolio across as many PCAF asset classes as possible.

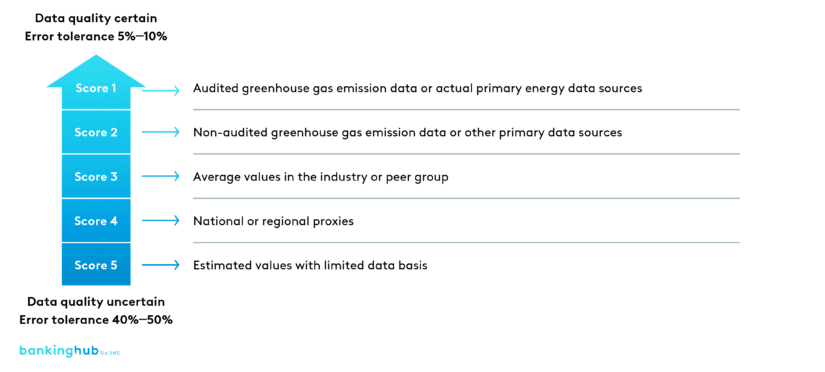

- Identifying data needs & data gaps: Second, data needs and potential data gaps for GHG emissions calculations must be identified for the PCAF asset classes to be calculated. According to the PCAF standard, different calculation approaches with different error tolerances are used depending on systemic data availability and data quality. While sectoral emission estimates have a rather high error tolerance (“improvable” data quality score), audited counterparty-level emission data have the lowest error tolerance (“ideal” data quality score). The data requirements for data quality scores targeted in the future should already be taken into consideration today.

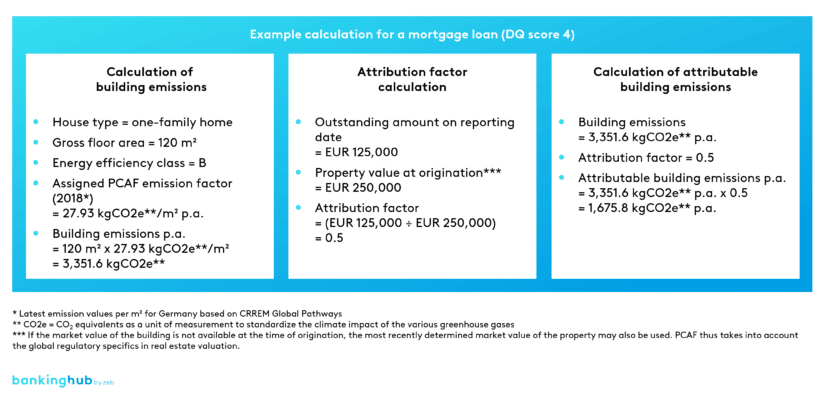

- Applying methods: In the third step, the slightly different calculation methods depending on PCAF asset class must be applied. Across asset classes, an attribution factor is used to determine the financial institution’s “fair share” of the financed business. For unlisted corporate customers, the attribution factor is derived from the ratio of the outstanding amount to the customer’s total equity and debt. For mortgage or commercial real estate customers, however, the outstanding amount is compared with the property value at origination. The determined attribution factor is then offset against the GHG emissions of the counterparty or the property.

In the PCAF methodology, emissions avoided by using renewable energy may not be netted against financed GHG emissions. Instead, PCAF recommends separate reporting of avoided emissions.

The following is an example of a mortgage loan.

If the gross floor area of the building is not available, blanket emission values for the respective building type can also be used at the expense of error tolerance (data quality score 5). In the above example, ideal data quality would exist if primary data were available on the actual energy consumption of the building (data quality score 1).

- Reporting & disclosure: While the disclosure of financed GHG emissions was initially voluntary in many countries, the requirements in this regard have recently become much more specific, particularly in Europe. In the future, smaller institutions will be required to disclose their financed GHG emissions under the CSRD in conjunction with the ESRS, while large institutions will also have to take into account the requirements of the EBA ITS on the disclosure of ESG risks (Pillar III). For the GHG-measuring financial institutions, regular disclosure has the advantage that it can be used for checking the plausibility of their own calculations and for benchmarking with the peer group. PCAF collects sustainability reports published by PCAF member banks on a central website for easy access.

Use of the PCAF standard is permitted even without officially joining PCAF as a member bank. By contrast, official PCAF membership – and with it the fully compliant approach to carbon accounting according to the PCAF standard – enables access to an extensive emissions database that offers, among other things, a differentiation by scope 1, scope 2 and scope 3 emissions per sector.

Operational challenges in carbon accounting

The following challenges require bank-specific solutions:

- Business segmentation: An institution’s financed business must be clearly segmented to correspond with the logic of the PCAF asset classes. It needs to be examined on an institution-specific basis to what extent the rating system/process used is sufficient or whether the intended use of funds or other indicators must be added.

- Data collection: Financial institutions that have not officially joined PCAF must rely on other emissions databases. While some emissions databases are based on the domestic concept (entities operating within a country’s borders), other databases use the national concept (entities domiciled within a country’s borders).

- Data gaps: When calculating attribution factors, it must be clarified how to deal with non-existent data on turnover, total assets and market value. For residential and commercial real estate where no gross floor area is available, it must be discussed on an institution-specific basis to what extent scaling can take place based on business with existing gross floor area or whether blanket building emission values “must” be used.

- Data processing: Calculation solutions in MS Excel tend to grow very quickly in terms of data volume, thus becoming slow and performing poorly, especially when GHG emissions are calculated for the entire portfolio. The extent to which specific database software solutions should be used or a data sample may be used instead of the entire data set needs to be clarified.

Even if the data repository is incomplete at the beginning and the calculation results still show noticeable fluctuation margins due to average data used, two main points apply. Firstly, the missing data should be collected and integrated into the data repository to gradually improve data availability and data quality. Secondly, even an initially less “precise” calculation can allow strategic analyses in connection with the target path toward “net zero” to be started.

Conclusion and outlook

Carbon accounting is not just a regulatory requirement. It has huge strategic importance for planning a GHG target path toward “net zero”. Carbon accounting is the starting point for operationalizing a reduction path for the respective sub-portfolios of a bank. It provides added value in risk analysis.

While data availability in carbon accounting is a challenge, it can be overcome with PCAF’s methodological framework (as well as any provisional “in-house” solutions).

It is important to gradually improve portfolio coverage and data quality over the coming years. For this reason, institutions should implement relevant measures as a matter of urgency.