|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

About the Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive (CSDDD)

This regulation fosters fair competitive conditions and provides legal assurance within the EU single market, which, however, have been distorted to the detriment of German companies, including banks, since the SCDDA. The CSDDD applies to large companies with 1,000 or more employees (in full-time equivalents) and a turnover of EUR 450 m (Art. 2) – with an incremental application from 2027 to 2029 – thus extending also to the financial sector (Art. 3).

Similar to the SCDDA, the CSDDD mandates the inclusion of affiliates when the parent company holds decision-making power over their management, operations, or financial affairs. In contrast to the SCDDA, the CSDDD also considers franchisors if their turnover exceeds EUR 22.5 m (EU) and EUR 80 m (worldwide) when granting rights to self-employed persons. Furthermore, the CSDDD extends its reach to companies established beyond the EU, with turnover thresholds exclusively tied to EU-based revenue.

What will change with the CSDDD?

The CSDDD significantly amplifies or modifies specific requirements for affected banks and savings banks in several areas, as we show below.

Expansion of the risk types taken into account and consideration of climate aspects

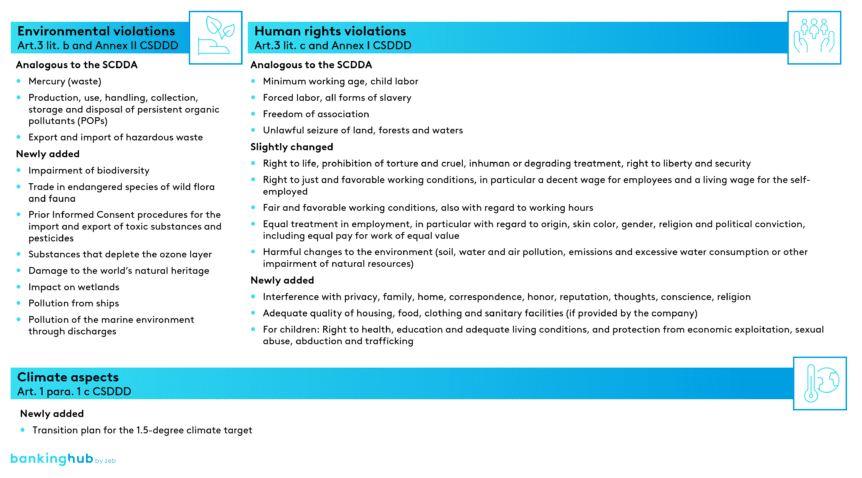

In contrast to the SCDDA, the CSDDD expands its scope to include risks related to environmental and human rights violations (see Figure 1).

These new considerations demand targeted strategic management. Art. 1, for instance, mandates the alignment of the companies’ business models with the Paris Climate Agreement’s goal of limiting global warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius. Companies subject to the CSDDD must draw up a so-called transition plan based on their respective strategy and business model (Art. 15). This plan aims to achieve the 1.5-degree target. Separate reporting, however, is not universally mandated (see the paragraph on reporting obligations).

Redefinition of the activity chain

In contrast to the SCDDA, the CSDDD not only considers direct suppliers but also indirect suppliers under Art. 3 lit. e. The latter become relevant if their activities are linked to the obligated company. At the same time, both upstream and downstream activities must be evaluated. The CSDDD therefore focuses on the value chain in two directions: downstream (upstream to suppliers) and upstream (downstream to suppliers) within the framework of the activity chain referred to therein (Art. 3 lit. g). However, downstream companies are only relevant if they carry out activities on behalf of or for the obligated company.

Companies from the financial sector, such as banks, need only assess their own activities and the upstream value chain (especially Annex 36b), similar to the SCDDA. The downstream value chain (e.g. in connection with the granting of loans) is excluded for the time being.

Due diligence obligations

The CSDDD places significant emphasis on companies’ duty of care concerning due diligence obligations. As part of a due diligence policy, for example, the due diligence-related strategies, a code of conduct and a process description must be firmly established. Similar to the SCDDA, the CSDDD addresses critical points such as risk assessment and prioritization, prevention, remediation, complaints procedures, documentation, effectiveness monitoring and reporting. Given the broader scope of risks covered by the CSDDD, it is reasonable to expect increased administrative efforts in risk management.

Stakeholder participation

While the SCDDA has only minimally addressed stakeholder consultation (e.g. involving a company’s own employees), the CSDDD imposes significantly more extensive requirements. Before creating a due diligence guideline, companies must either consult their employees or seek expert advice (Art. 5). The participation process may impact the speed of CSDDD implementation. The increased need for coordination should therefore be taken into account from the outset.

Reporting obligations

Reports submitted annually by obligated companies are published in the European Single Access Point (ESAP) (Art. 11a). In the event that a non-financial or a CSRD report is required, the legislator avoids duplication by not mandating separate reporting (Annex 44). Banks, in particular, benefit from this simplification.

Liability and compensation

Unlike the SCDDA, which relies solely on fines and exclusion from public contracts, the CSDDD introduces liability for damages. However, the fines can now reach up to 5% of the affected company’s annual turnover (Art. 20). A new for supervisory authorities to consider when calculating fines is “compensation”. Companies must factor in claims for damages as an additional ESG risk in their risk management.

BankingHub-Newsletter

Analyses, articles and interviews about trends & innovation in banking delivered right to your inbox every 2-3 weeks

"(Required)" indicates required fields

When and how will the CSDDD be transposed into national legislation?

The CSDDD is anticipated to be transposed into German law through amendments to the existing SCDDA. In the interest of regulatory stability, it is reasonable to assume that stricter regulations will be integrated into the SCDDA without withdrawing any existing provisions. This alignment is supported by Art. 1 para. 2 CSDDD, which prohibits reducing a higher level of protection provided by a Member State’s law. Regarding the date and scope of application, we can infer that in Germany, as before, companies with 1,000 or more employees (in headcount) will remain subject to the regulation, irrespective of their turnover.

Conclusion: It is advisable to address the tightening measures at an early stage!

Even though the more stringent provisions of the CSDDD are not yet in effect under the German SCDDA, we recommend that banks exceeding the 1,000-employee threshold (directly affected), or likely to do so within the next two years, address the extended CSDDD due diligence obligations early. For banks and savings banks below the 1,000-employee threshold (indirectly affected), a “trickle-down effect” applies, according to which larger companies can ensure comprehensive compliance with due diligence obligations by smaller contractual partners through contractual clauses.

From a risk orientation perspective, all banks must ensure to dovetail the topic of CSDDD is dovetailed with their respective business, risk, and sustainability strategies. This alignment is relevant for several reasons:

- When granting loans, banks and savings banks may encounter ESG risks in the borrower’s value chain. These risks may manifest as credit risks, particularly in the form of social risk factors. For instance, customers may be subject to penalties in the event of non-compliance with due diligence obligations.

- It is possible to exclude risk sectors (e.g. textiles) from the risk strategy as part of a blacklist. Alternatively, these sectors can be subjected to tighter ESG-related lending guidelines (e.g. additional documentation requirements).

Banks must also address the sustainable transformation of their environment as part of their business area analysis (MaRisk AT 4.2). CSRD and CSDDD offer an opportunity to gather valuable information from larger corporate customers. While only a portion of corporate customers may be impacted by the CSRD or CSDDD requirements, those “large” corporate customers in the region that are affected (possibly typical hidden champions) will also record and report on their regional and local suppliers as a factor influencing their transition plan and thus allow preliminary conclusions to be drawn about the transformation of the banks’ respective business areas.

Finally, customers can reasonably expect that their own bank – even if it employs fewer than 1,000 people – avoids environmental or human rights violations in its own value chain.

In conclusion, regardless of the financial institution’s size, we recommend thoroughly examining the CSDDD from a reputational standpoint. This recommendation holds even if policymakers consider suspending the SCDDA, as currently discussed in the press.