|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

|

LISTEN TO AUDIO VERSION:

|

The EU taxonomy’s relevance in institutions

The classification as “sustainable” affects a number of EU regulations with different requirements.

Reporting and disclosure

With regard to non-financial reporting, Article 8 of the EU Taxonomy Regulation provides for the addition of qualitative and quantitative sustainability aspects. According to the NFRD[1], non-financial reporting applies to large public-interest companies with more than 500 employees. The CSRD[2] extends the scope of its application to all large companies.

For credit institutions, a delegated act specifies green asset ratios (GARs), on the basis of which the sustainability of bank assets must be reported in varying degrees of granularity. The taxonomy is used to assess the sustainability of the portfolio. Likewise, large institutions are required to make Pillar 3 disclosures of GARs.[3] The provided templates are similar to the non-financial reporting requirements.

Product-related classification and information

For the Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation (SFDR), the taxonomy determines whether a financial product may be classed as sustainable. It is then referred to as an “impact product” according to Article 9 of the SFDR. Financial products in the area of investment advice and portfolio management are especially suitable for this purpose. A number of additional disclosures must be made for financial products that are offered as “sustainable”.

The assessment of the sustainability of products is also important when providing advisory services to customers according to MiFID II. The terms of the directive stipulate that the sustainability preferences of customers and the products’ sustainability characteristics are to be included in the advisory service.

The EU Green Bond Standard (EU-GBS) is intended to create a label for the sustainability of bonds. The present draft stipulates that in order to apply the label “EU-GBS” the use of funds has to conform with the EU taxonomy.

BankingHub-Newsletter

Analyses, articles and interviews about trends & innovation in banking delivered right to your inbox every 2-3 weeks

"(Required)" indicates required fields

EU taxonomy: assessment scheme for sustainable investments

For an investment to be classified as sustainable, it must both serve an environmental objective and not harm any other environmental objective. In addition, it is required that minimum social safeguards defined in Article 18 of the Taxonomy Regulation are ensured. This refers to existing publications such as the International Bill of Human Rights.

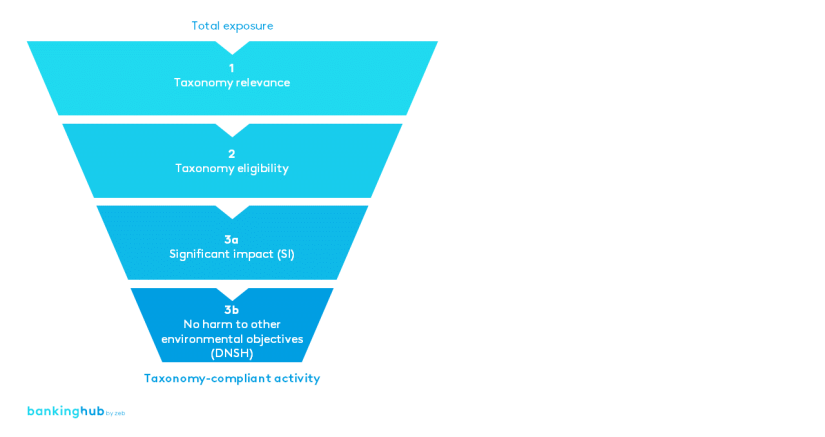

Essentially, the criteria for assessing the taxonomy alignment of economic activities can be divided into three steps, as illustrated in fig. 1.

The first step is to determine the extent to which the activity under consideration is included in the current scope of the EU taxonomy (taxonomy relevance). Central and regional governments and public authorities, for example, are currently excluded. The reasoning behind this is above all the lack of sufficient information to determine taxonomy alignment.

In the second step, the taxonomy eligibility of the respective economic sector is assessed on the basis of the NACE code. Only those economic sectors are taxonomy-eligible which are explicitly mentioned in one of the lists published by the EU Commission. At present, companies or institutions from 136 economic sectors are generally considered taxonomy-eligible.

The third step then involves an initial assessment of the extent to which the economic activity makes a substantial contribution to the fulfillment of at least one of the six environmental objectives listed in Article 9 of the Taxonomy Regulation.

The environmental objectives of the EU taxonomy are:

- Climate change mitigation

- Climate change adaptation

- The sustainable use and protection of water and marine resources

- The transition to a circular economy

- Pollution prevention and control

- The protection and restoration of biodiversity and ecosystems

At the moment, explicit assessment criteria only exist for the environmental objectives of “climate change mitigation” and “climate change adaptation”. These are defined individually for each taxonomy-eligible economic activity.

If the economic activity makes a substantial contribution to one of the environmental objectives, a final review is conducted to ensure that it does not harm any of the other five environmental objectives. For this purpose, individual “Do no significant harm” (DNSH) criteria are defined for each economic activity and for each of the environmental objectives. If no condition causing significant harm as defined by the DNSH criteria applies and the minimum social safeguards from Article 18 of the Taxonomy Regulation are ensured, the economic activity is classed as taxonomy-aligned.

Therefore, to be taxonomy-eligible, economic activities have to meet a variety of criteria. A study by the European Commission’s Joint Research Centre (JRC) using data from 2020 concludes that only 0.3% of the banking sector’s investments would be classed as taxonomy-aligned.[4]

How banks can effectively determine the proportion of their exposure that can be regarded as taxonomy-aligned is examined in more detail below, using an example from the real estate lending business.

Assessment of taxonomy alignment in the real estate sector

Taxonomy eligibility is determined at the level of the individual taxonomy-eligible economic activity. For banks that operate various taxonomy-eligible economic activities, the assessment according to the EU taxonomy may not only involve a high degree of complexity, but also require a large number of assessment activities. In view of the shortage of resources as regards time, data and budget, a step-by-step assessment approach is recommended.

Institutions should first start with the taxonomy assessment of those items that contribute most to the balance sheet total. In the case of building societies or banks that focus specifically on real estate loans, it thus makes sense to prioritize the assessment of these economic activities.

The real estate business in various forms is already defined as taxonomy-eligible for both environmental objectives and is therefore especially well suited as an example. The high relevance of the real estate business also arises from the involved savings potential. The real estate sector accounts for almost 40% of greenhouse gas emissions in the EU and Germany.

First of all, the taxonomy’s technical assessment criteria provide for seven financing categories in the real estate or construction sector. These range from new constructions and renovations to building acquisitions, the installation of equipment and technological upgrades.

As fig. 2 illustrates for the environmental objective of “climate change mitigation” of the EU taxonomy, the scope of the taxonomy alignment assessment in some cases varies considerably between the individual categories. For instance, new constructions have to meet the most extensive criteria. Their assessment requires a great deal of information about the property in order to prove a significant impact (SI). The required information includes an energy performance certificate (EPC, which serves as a statement of the overall energy efficiency), information on air tightness and thermal performance, and proofs regarding global warming potential (GWP).

In contrast, the assessment criteria for the installation of equipment and technological building upgrades are less extensive. As part of the step-by-step approach, it is advisable to start with the financing categories since they require a less comprehensive assessment. This is the case for those financings where fewer criteria have to be met and the necessary data for verification is available. Especially with regard to data availability for the assessment of new business, it is important to start collecting the relevant data at an early stage.

Figure 2: Overview of technical assessment criteria for real estate to meet environmental objective 1: climate change mitigation

Figure 2: Overview of technical assessment criteria for real estate to meet environmental objective 1: climate change mitigationIn addition, the complexity of the assessment may be reduced by leveraging synergies relating to data requirements. Three of the seven financing categories in the real estate sector, for example, rely on similar data requirements, such as the energy performance certificate, to prove a substantial contribution.

The main challenge, aside from the assessment of the significant impact (SI criteria), is the assessment of the DNSH criteria. In fig. 2, the alphabetic characters a to e refer to the assessment of whether harm is done to any of the other environmental objectives (a to e, respectively, represent environmental objectives 2 to 6). When assessing the DNSH criteria, credit institutions should increase the level of ambition gradually and, if necessary, work with reasonable estimates at the beginning. Supervisors have also acknowledged that the effort involved in assessing the DNSH criteria is very high.[5]

The EU taxonomy: conclusion – consistent examination still necessary

As demonstrated in the previous statements, the taxonomy’s impact is already high and needs to be embedded in the processes of many institutions. It is important to bear in mind that the sustainability classification of investments can currently only be carried out on the basis of two of the six environmental objectives. Four more environmental objectives are pending. If these are included, this will increase the complexity and effort involved in obtaining data. On the upside, it also enables a larger proportion of the portfolio to be classified as sustainable. Finally, some further developments such as the drafting of a “social taxonomy” are still pending.

In summary, it is crucial for institutions to continue to take a holistic approach to integrating the requirements from the taxonomy into internal processes. The following holds true: the sooner institutions deal in-depth with the challenges of the taxonomy, the more likely they are to succeed in integrating the topic of sustainability holistically into their processes.