|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

Robust US economy and interest rate cuts bolster capital markets

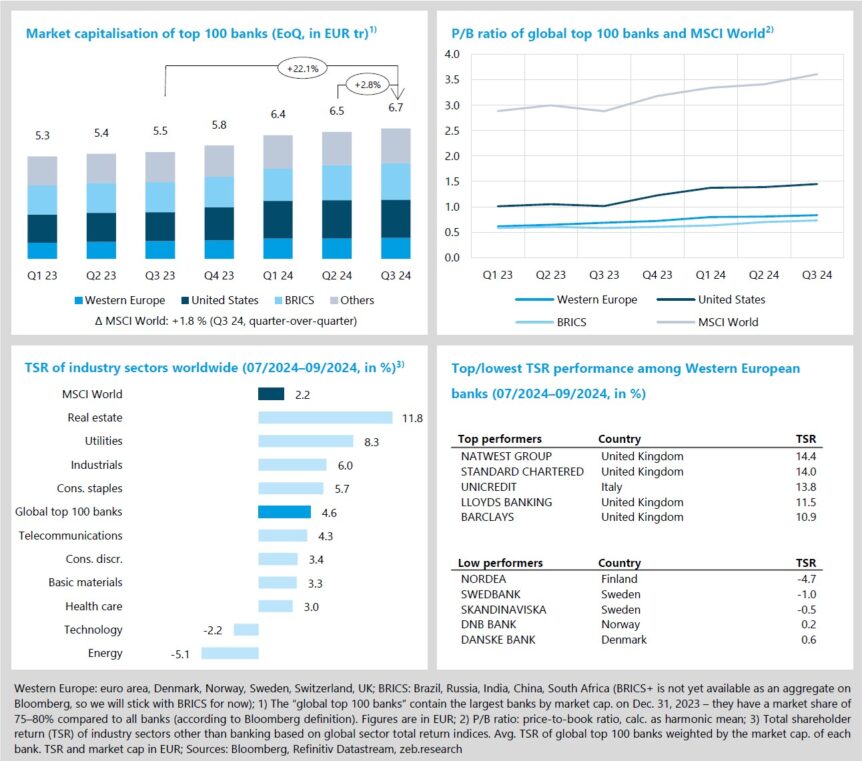

- The solid TSR performance of the global top 100 banks (TSR +4.6% QoQ) is driven primarily by banks from Western Europe (+5.0% QoQ).

- The increase in the price-to-book ratio (P/B ratio) of US banks (+0.06% QoQ) widened the gap to Western European competitors (+0.03x) in Q3 24.

An upswing in the US economy – after initially weak economic data – combined with key interest rate cuts by the most important central banks have led to an additional slight upturn on the global capital markets in Q3 24 (MSCI World market cap +1.8% QoQ, TSR +2.2% QoQ). The solid TSR performance of the global top 100 banks (TSR +4.6% QoQ) was driven primarily by banks from Western Europe (+5.0% QoQ) and BRICS (+6.7% QoQ) (USA: +0.8% QoQ). The end of the high-interest phase – heralded first by the ECB, recently followed by the US Fed – remains one of the key future challenges for banks.

- The price-to-book ratio rose in Q3 24 for banks from all regions under review, with US banks recording the largest increase (+0.06x QoQ to 1.45x; Western Europe: +0.03x QoQ to 0.84x).

- Benefiting from the end of the high-interest phase, the real estate sector took first place in the industry sector ranking in Q3 24 with a TSR performance of +11.8% QoQ. At the bottom of the list is the energy sector (TSR -5.1% QoQ), which had to contend with dwindling investor confidence due to falling demand for oil and declining prices.

- With a TSR of +14.4% QoQ, NatWest once again leads the ranking of Western European top performers in Q3 24. In Q2 24, the bank exceeded the forecast operating profit of EUR 1.26 billion by more than EUR 400 million. In the wake of UniCredit’s acquisition of an equity stake in Commerzbank and subsequent speculation about a hostile takeover, the Italians achieved a TSR of +13.8% QoQ. This makes them the only non-UK based institution among the top performers.

US Fed follows ECB into interest rate turnaround

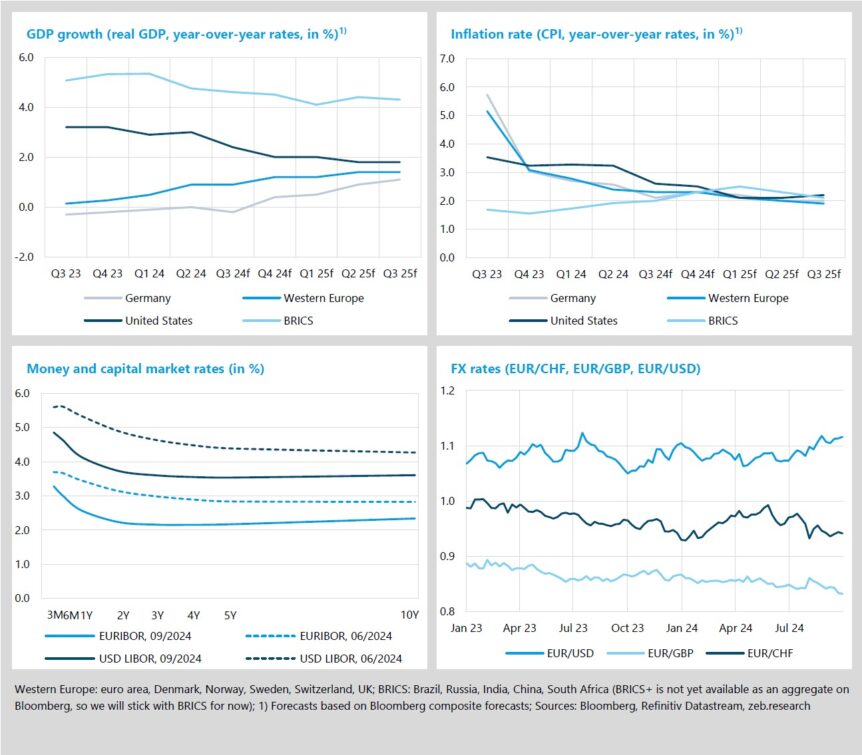

- In Q3 24, the inflation rate in Germany declined once again and, at 2.1% YoY, almost reached the target rate of 2%.

- The yield curves in both the euro and US dollar zones shifted downwards in Q3 24, with inversion decreasing at the same time.

After recent more optimistic GDP forecasts, the outlook for Germany has once again turned gloomy. Contrary to the recently expected growth of +0.1%, the markets are now anticipating a decline in GDP of -0.2% for Q3 24. While growth in Western Europe is expected to remain unchanged (Q3f: +0.9%), the US economy is experiencing a slight upturn compared to earlier forecasts (Q3f: +2.4%).

The USA is also edging towards the target inflation rate of 2% (Q3f: 2.6%), with the markets expecting an inflation rate of just 2.1% for the USA and Western Europe as early as Q1 25. The ECB and the US Fed used the leeway that had become available to begin the renewed turnaround in interest rates. The US Fed’s sharp interest rate cut of 50bp in September led the markets to briefly speculate on a similarly drastic next step. The ECB has hinted at another key interest rate cut for October.

- For Q3 24, Germany can expect a significant decline in the inflation rate by -0.5%p to 2.1% YoY compared to the previous quarter (Western Europe: -0.1%p to 2.3% YoY).

- As a result of the key interest rate cuts by the ECB and the US Fed, the yield curves shifted downwards in both the euro and US dollar zones. It is striking that the inversion – a classic indicator of an emerging recession – decreased in both curves. Notably, 10-year interest rates are currently exceeding 2-year rates in the eurozone again– however, this is not yet the case in the USA.

- The appreciation of the euro against the US dollar in Q3 24 resulted primarily from the surprisingly sharp interest rate cut by the US Fed in September. By contrast, the Bank of England is currently acting relatively hesitantly, having only initiated a 25bp interest rate hike to date despite low inflation in the UK. Accordingly, the EUR/GBP exchange rate fell in Q3 24.

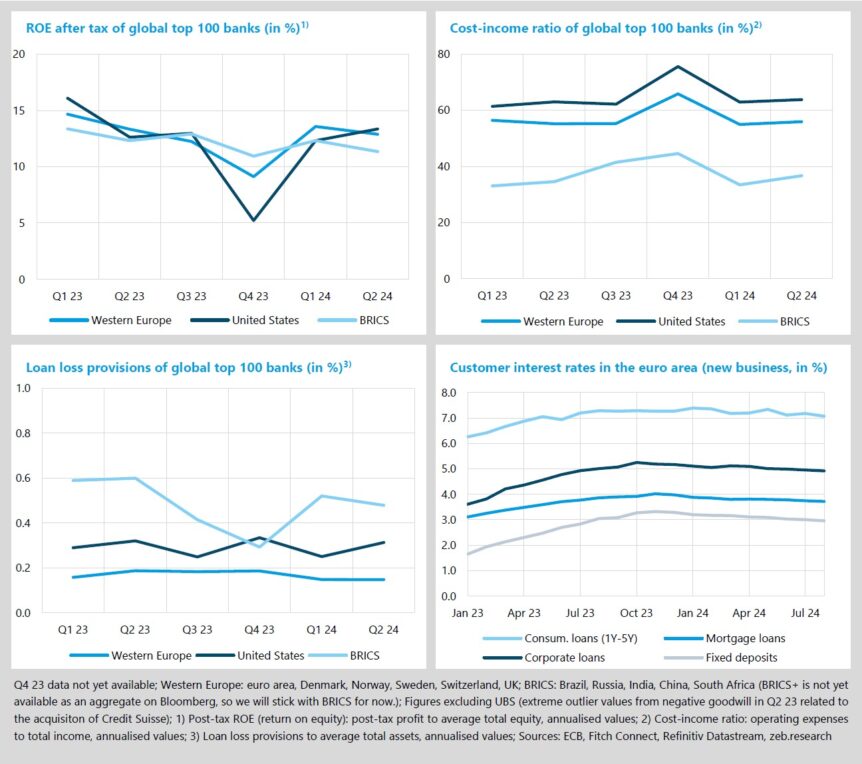

After occupying last place in the ROE ranking of the regions under review for two quarters in a row, US banks saw 1.0%p ROE growth QoQ, resulting in the highest ROE in Q2 24 of 13.3% (Western Europe: 13.1%; BRICS: 11.3%). Only the US banks were able to increase their profits compared to the previous quarter. Among other things, this was due to the fact that commission income offset the lower net interest income compared to the previous year and that individual large banks realised one-off securities gains from Visa stocks held since the IPO.

The ROE decline at Western European banks of -0.5% QoQ was, however, slowed by comparatively robust net interest income and net commission income.

- After the banks in all regions under review experienced ups and downs in terms of their cost-income ratios in Q4 23 and Q1 24, the figures stabilised in Q2 24. Western European banks recorded a rise in their cost-income ratio of +1.0 %p QoQ to 55.4% (US banks: +0.9 %p to 63.8%). While this increase at Western European banks was driven exclusively by rising costs (+3.7%p QoQ), US banks reported a decrease in costs of -1.9%p QoQ accompanied by a drop in income of -3.4%p QoQ.

- While the risk provisioning of Western European banks remained unchanged in Q2 24, US banks increased their loan loss provisions by +6bp QoQ. This primarily reflects the dire situation on the market for office real estate and high write-offs on credit cards. At the same time in Q2 24, economic data published in the meantime suggested a noticeable downturn in the US economy.

- Customer interest rates in the euro area continued their gradual decline and, in view of further ECB interest rate moves in the foreseeable future, have in all likelihood not yet reached the end.

BankingHub-Newsletter

Analyses, articles and interviews about trends & innovation in banking delivered right to your inbox every 2-3 weeks

"(Required)" indicates required fields

The biodiversity crisis – an underestimated challenge

(extended article to mark the 50th anniversary of zeb.market.flash)

- The biodiversity crisis doesn’t announce itself with hurricanes and forest fires, but grows quietly and insidiously – which is what makes it so dangerous.

- Preserving species also means preserving collective prosperity – and banks play a key role in this.

The biodiversity crisis is one of the most pressing but often neglected threats of our time. The topic of biodiversity often gets overshadowed by climate change and carbon emissions, which have long since become an integral part of economic and political discussions. However, the economic implications of the loss of species and the destruction of ecosystems are enormous.

In light of the immense importance of “natural assets”, tackling these issues is becoming ever more of a necessity, also for the financial industry. Banks and other financial players play a crucial role in promoting sustainable practices through investment and lending decisions and in helping to overcome the biodiversity crisis. Whether through targeted investments in projects that support the preservation and restoration of ecosystems or the consideration of biodiversity risks in lending decisions – financial institutions can make an impact in many different ways.

But how well are banks prepared for this challenge, and how can they live up to their responsibility of safeguarding the capital value of natural assets in the long term?

How much do European banks need to do in terms of ESG? Download our ESG Implementation Study!

ESG Implementation Study 2024

Europe’s banks under the microscope: between ecological ambition and economic realityDiversity of species – a vital asset

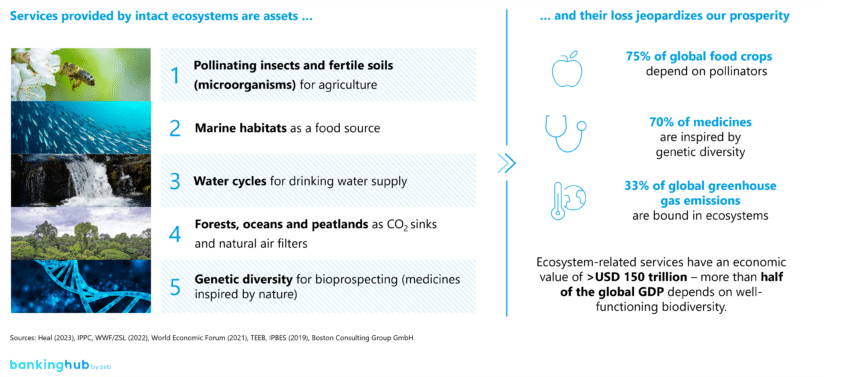

Many people are unaware that an intact biodiversity is a crucial basis for a large number of ecosystem-related services that they use on a daily basis (see Fig. 1).

The loss of biodiversity is therefore not just an ecological crisis, but also an economic threat. Much of the damage develops gradually and is therefore difficult to measure, but it ultimately results in considerable costs for the entire world’s population. Humankind takes the services offered by nature for granted because they are usually free and seemingly unlimited. However, nature’s limits have long since been exceeded.

Since 1970, the world’s population has grown by 112%, which has strongly increased the demand for natural resources. This is also reflected by various factors that threaten biodiversity: in this period, meat production has increased by 244%, raw material production by 193% and carbon emissions by 146%. At the same time, the wild animal population declined by an alarming 69% (with some regions of the world being particularly affected – South America, for example, experienced a 94% decline).

Tackling the biodiversity crisis is closely interlinked with the global efforts to combat climate change. Ambitious targets have been set by 2050 to tackle the complex challenges of both climate and species protection, namely net-zero emissions and nature positivity (a net gain in biodiversity). To achieve those, both targets need to be worked towards simultaneously and in a coordinated manner.

Climate and species protection measures are mutually dependent and mutually reinforcing. The biodiversity crisis is further exacerbated by climate change and underlines the often neglected impact of global warming on biodiversity. Achieving the “net-zero” targets early and consistently will help to limit the loss of habitats and curb the spread of invasive species. At the same time, the promotion of “nature positivity” through reforestation and the protection of natural habitats contributes to the reduction of carbon emissions.

Nevertheless, there are various aspects that clearly make combating the biodiversity crisis a lot more complex than that. The non-linear relationship between anthropogenic pollution and biodiversity results in complex, unpredictable effects on networked ecosystems. By contrast, the climate crisis is based on a monocausal relationship (more emissions result in more warming). Moreover, it is usually not possible to offset the loss of one habitat’s key species in another habitat – instead, all biodiversity measures require a region-specific approach, as no two ecosystems are the same. The climate crisis, on the other hand, can be tackled with the same measures in all regions of the world (renewable energies, reforestation /peatland rewetting, direct air capture, …).

One of the crucial intentions behind this article is to make a clear distinction between what players from the financial industry can do to meaningfully tackle the biodiversity crisis and promote decarbonisation, respectively. Let us start with an economic framework that illustrates the necessity to restructure lending and investment portfolios in a particularly vivid manner.

Political ambitions and economic responses

In recent years, the conservation of biodiversity has been given ever more political importance. At an international level, both the United Nations (UN) and the European Union (EU) have committed to the issue: The UN’s 17 Sustainable Development Goals include a total of six goals that are directly linked to biodiversity, including the availability of clean water, the preservation of life under water and on land, climate protection and the sustainabilisation of cities and communities.

The European Union has developed its own biodiversity strategy for 2030, which provides for the protection of at least 30% of its land and sea areas. The European Sustainability Reporting Standards 4 (ESRS4) that specify how to comply with the Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD) require companies and financial services providers to disclose how their activities affect biodiversity and ecosystems and the extent to which their activities depend on nature.

At national level, however, the picture is rather mixed. In Germany, for example, the federal government has updated its “National Strategy on Biological Diversity 2030” with clearly defined key measures for promoting near-natural land use and strengthening the management of protected areas. However, while the intended measures for tackling the climate crisis are nothing short of a holistic transformation of the economy, the practical implementation of the biodiversity strategy doesn’t live up to the ambitions in many regards. However, holistic economic framework concepts have long since been developed.

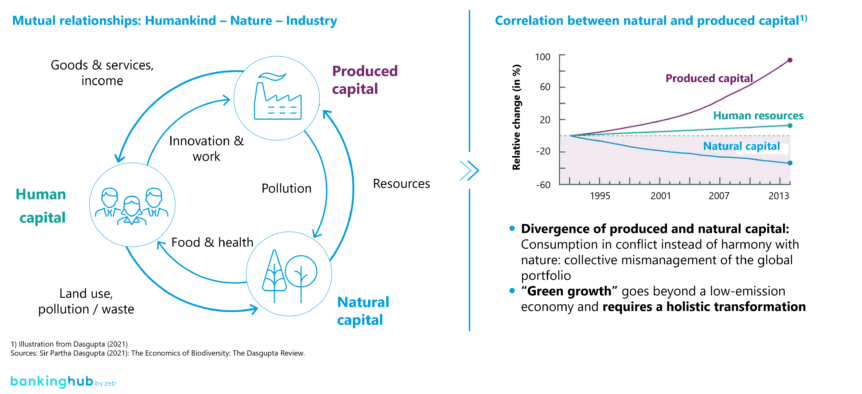

The Dasgupta school, for example, regards biodiversity as natural capital, i.e. another essential asset alongside human and produced capital. The cycle diagram (Fig. 2) highlights the reciprocal relationships between people, nature and industry and emphasises the need for an integrative understanding of sustainable management.

There are three recommendations for reshaping the economic framework that are aimed at helping humankind think of natural and produced capital in a way characterised by mutual respect:

- reshaping our financial and educational systems,

- reducing the demand for services provided by nature while increasing the supply thereof, and

- changing the way we measure economic success.

The third recommendation requires some explanation: according to Dasgupta, GDPs do not properly represent economics in that they do not take into account the depreciation of assets, for example through the destruction of the biosphere. Dasgupta argues that GDPs, as the primary measure of economic success, encourage the pursuit of unsustainable economic growth. To counteract this, Dasgupta proposes “Integrative Wealth” as an alternative, more coherent quantification of wealth that is based on all three types of assets shown in Fig. 2. In 2022,

Frank Elderson, Member of the Executive Board and Vice-Chair of the Supervisory Board of the ECB, explained: “Since we have explicitly recognised the materiality of nature-related financial risks, it is no longer a matter of principle that the work on environmental risks is less advanced than the work on climate.”

However, the picture is different for players in the financial sector. In a survey by PwC (2022), 83% of respondents stated that biodiversity plays a minor or very minor role in their industry. The following chapter illustrates that the opposite is the case.

“The next big thing” for banks?

The regulatory achievements in response to the climate crisis are increasingly emerging as a blueprint for how banks will need to systematically address the biodiversity crisis in the future – starting with risk inventory (classified into physical and transitional risks), determining their materiality, all the way to testing risk-bearing capacity and subsequent risk control. The ECB has already recognized the biodiversity crisis as a fundamental risk driver, and the concretization of regulation has begun.

It is expected that, like with the climate crisis, the “Network for Greening the Financial Sector” (NGFS) will be called upon to provide the scientific basis for stress test scenarios. According to ESRS E4, the resilience analysis described there will soon require calculations on how much capital could be consumed in these stress tests due to biodiversity risks (default risks) and whether capital requirements (ICAAP) will remain attainable.

Physical risks arise directly from the loss of biodiversity and the associated ecological changes. They affect banks in particular through their impact on the companies and assets in which banks invest or to which they grant loans.

For example, the reduction of biodiversity can significantly affect the productivity and resilience of sectors such as agriculture, fisheries, tourism and forestry. A case in point is the decline in pollinators, which leads to lower yields in agriculture, which in turn negatively affects the creditworthiness and profitability of agricultural businesses that rely on such services. Similarly, floods or other natural disasters, the frequency and intensity of which are exacerbated by the loss of ecosystems such as mangroves or coral reefs, can cause considerable damage to real estate and infrastructure financed by banks. These physical risks can result in loan defaults and losses in the value of banks’ portfolios, as companies in affected sectors are no longer able to service their liabilities.

Transitory risks pertain to the adaptation costs and market changes resulting from the transition to a more biodiversity-friendly and sustainable economy. These risks arise from regulatory changes and technological developments as well as changing market conditions and social expectations.

Banks could, for example, be affected by strict regulation aimed at protecting biodiversity, such as new reporting requirements or requirements regarding the financing of sustainable projects. Companies that have a considerable negative impact on biodiversity could be confronted with higher operating costs, loss of sales or even the freezing of investments due to such regulatory measures.

For banks, this means an increased risk of credit defaults or losses in value if the underlying assets turn out to be less valuable or riskier. In addition, technological innovations and changing consumer behaviour could influence the demand for certain products or services, thus causing market shifts that force banks to adjust their investment strategies and risk assessments.

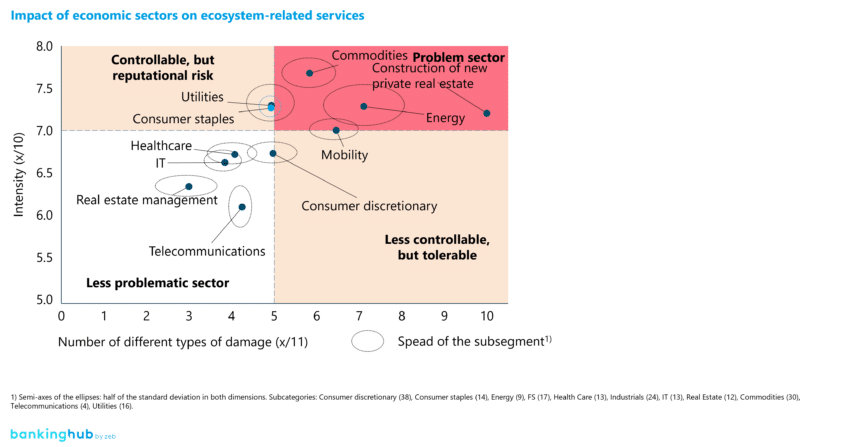

If stress scenarios under physical and transitional risks prove to be capital-consuming, a credit portfolio analysis becomes essential. Fig. 3 segments different economic sectors in the credit portfolio based on the number (eleven different types of ecosystem degradation, e.g. water use, soil sealing, greenhouse gas emissions and marine pollution) and intensity of damage to ecosystem services.

The top right area of the graphic indicates the problematic industries. These primarily include the commodities and energy industries as well as the construction of new private and – to a lesser extent – institutional real estate. These industries exhibit both a high intensity of damage (y ≥ 75 %) and a wide variety of types of damage (x ≥ 7 out of 11). These problematic industries are particularly relevant for large banks that invest in alternative assets. Investments in commodities or infrastructure projects as well as loans for real estate construction are heavily affected by the biodiversity crisis.

The figure also highlights the remarkable heterogeneity within the different industries, especially w.r.t. industries such as energy and construction materials. These industries show a wide spread in terms of the types and intensities of damage. The zeb.research analysis made it clear that even sub-industries that are considered part of the solution and not the problem from a climate perspective (e.g. in the energy sector: hydropower, biogas plants, offshore wind farms), can pose significant risks to biodiversity and the associated ecosystem-related services.

To account for this complexity, banks need to expand their risk management processes and reporting obligations and take measures that focus on more than their net-zero ambitions. The EU taxonomy is essential for channelling investment in these problem sectors. Although the current EU taxonomy is strongly focused on climate-related criteria, it is becoming apparent that biodiversity criteria, too, will continuously gain in importance.

Conclusion: The biodiversity crisis – “The next big thing” for banks?

To put it in a nutshell, banks play a decisive role in the biodiversity crisis. As financial intermediaries, they have a significant impact on which industries get funded and therefore bear considerable responsibility for the resulting impact on ecosystems.

The current state of research paints a clear picture: it is not enough to simply aim for the reduction of carbon emissions (“net zero”) – low-carbon industries that pollute the environment must also be closely scrutinised. Banks have a double moral imperative to make a difference considering their far-reaching impact on how humankind deals with the two global crises. Their actions not only determine their own resilience to ecological crises, but also have far-reaching and irreversible effects on the global environment and society.

“The next big thing?” – only to a limited extent: The climate crisis and the biodiversity crisis are two sides of the same coin when it comes to restoring natural capital. The requirements of the latter are often still insufficiently considered compared with those of the former. And yet the biodiversity crisis is just one facet of the non-negotiable and time-critical ESG transformation that is increasingly moving into the collective consciousness.